The School-to-Prison Pipeline for Children of Color with Disabilities: How Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions is Helping to Diversify the Fight

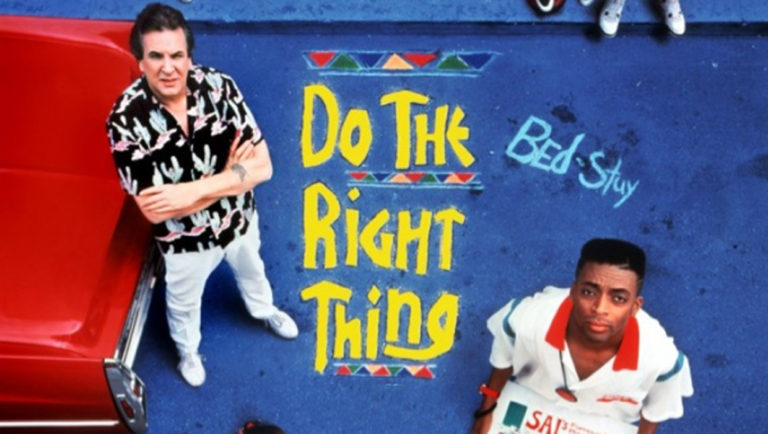

This year marks the 25th Anniversary of Spike Lee’s iconic film, Do the Right Thing. I recently watched it on cable for what seems like the hundredth time. One of my favorite scenes is when the character Buggin’ Out (played by Giancarlo Esposito) is eating a slice in his neighborhood pizzeria, in his predominantly African-American Brooklyn community, and challenges the Italian owner Sal (played by Danny Aiello) with the question that would set the stage for the movie’s pivotal moment:

“Hey Sal, how come you don’t got no brothers on the wall here?”

The question expresses Buggin’ Out’s resentment at not seeing photos of any black or brown people – “people” that looked like himself

– on the Wall-Of-Fame in Sal’s shop that he regularly patronizes. Tension builds, heated words are exchanged, drama ensues – end scene.

The films depiction of this incident speaks to our need to feel included; our desire to see ourselves reflected in and represented by those institutions that share space in our communities. And, the animosity that can build when we don’t see anyone that looks like us – our identifying group – on that institution’s proverbial wall, or at the discussion table in the board room, or at the workplace, or in the classroom, etc.

Similarly, the issue of ethnicity came up at last month’s National Council on Disability / Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund’s meeting focusing on the School-to-Prison Pipeline for Children of Color with Disabilities. In particular, the discussions centered on the overuse of the “10 Day Rule” discipline provision of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) which permits schools to remove a student with a disability from school for up to 10 days – providing an all too convenient justification for getting rid of students with disabilities without an assessment (i.e., IEP team meeting, behavioral intervention plan, functional behavioral assessment) or any other service or support. To put it another way, the 10 Day Rule constructively harms the very students the IDEA was intended to help. Unsurprisingly, the Rule tends to disproportionately impact children of color.

Which is why the issue of ethnicity is so ironic in this instance because while Latinos make up one of the fastest growing populations in the country, and are disproportionately overrepresented in the juvenile justice system, there was apparently only one Latino person in attendance at the meeting. And it was that lone Latino who made a point of posing the rhetorical question out loud to the group, in true “Do the Right-Thing”-esque fashion, “why are there no other Latinos in the room”? Furthermore, young people – as in high school age youth – were another key group noticeably absent from the event as someone else quickly pointed out. And while the temperature of the room remained congenial rather than accusatory (no garbage cans were thrown as in the movie) the passionate discourse that followed concerning the lack of Latinos and missing youth voice at this otherwise diverse meeting, was powerfully candid. In other words, the conversation turned very real!

“Nothing About Us, Without Us”

Diversity, or the lack of, is something we all like to think we are adequately sensitive to. I know what it’s like to be in a professional setting and be the only African American in the room. I recognize how important it is to have the active involvement of other people of color in the planning of strategies and policies that affect our lives. Having worked in the adult and juvenile reentry worlds, I understand why it’s critical to have input from formerly incarcerated people when the subject is criminal justice policy reform. I also get how absurd it would have been to not have people from the disability community well represented at this meeting. Yet, in all my ‘sensitivity’ I failed to immediately recognize and address the elephant in the room – that, youth and Latinos were almost entirely absent, adding particular irony to any discussion about school discipline for children of color, let alone those youth with disabilities.

This is not an indictment of the efforts to assemble a diverse audience. On the contrary, many of the guests – present company included – acknowledged that this meeting was one of the most racially diverse gatherings they had ever attended on the subject of disability. But diversity is more than race, and diversity is not the same as inclusion. And when it comes to inclusion, we are all complicit when we fail or even inadvertently neglect to recognize the voices that are missing from the conversation. Part of our due diligence as practitioners fighting for juvenile justice reform and disability rights is to make sure that whenever we sit down to formulate policy recommendations, the following questions are always asked: “who” else needs to be involved in the discussion; “why” are they not here; and “what” needs to be done to get and keep them involved. There is no moral victory in merely being more diverse or inclusive than in years past. Broader diversity and inclusion along a range of individual variables (i.e., types of disabilities, ethnic background, gender, age, etc.) is the necessary precursor to any meaningful progress for students with disabilities. More importantly, the issues surrounding race, ethnicity and disability are often inseparable as the stigma and discrimination that correlate with any one of these designations is palpable by itself. When you combine racial and disability discrimination together, the results are devastating for school children as multiple school suspensions reduce the chances of graduation from high school and increase their chances of incarceration.

Given the disproportionate number of youth with disabilities caught in the juvenile justice system, it is important to identify specific interventions that address their many needs for successful transition. The National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth’s Making the Right Turn: A Guide About Improving Transition Outcomes for Youth Involved in the Juvenile Corrections System highlights experiences, supports and services that all youth need, and distinguishes the particular needs of youth in the juvenile justice system. IEL’s Right Turn Career-Focused Transition Initiative (Right Turn) is based on the Guide along with other IEL-created foundational materials, and is currently being implemented across the country in five communities.

Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions (Beverly Hills, CA) founder and CEO, Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu states, “Understanding, implementing and ensuring greater diversity and youth voice along the adult-youth partnership spectrum expresses the conviction of people with disabilities, and people of color, and people of different ethnicities, and formerly incarcerated people, etc., that they all have particular insight into what is best for them and are ultimately the agents of their own progress. I have fought most of my academic and professional career, for the rights of children of color with severe and emotional disabilities…because no-one else would!” That said, it’s important to also realize that diversity and inclusion are ongoing journeys rather than finite destinations. As leaders in the juvenile justice reform and disability rights movements attempting to curb the School to Prison Pipeline, we must always be mindful to ensure that our brothers (and sisters) “on the wall” are present and part of every conversation that affects them.

By Byron Kline, Project Manager for the Right Turn Career-Focused Transition Initiative at the Institute for Educational Leadership’s Center for Workforce Development