For some Washington students with special needs, diagnosis is too late, help is too little

Something is not right.

When Luckisha Phillips’ son Jayden picked up a pencil in kindergarten, his letters often came out backward and inverted, so illegible that his mother thought something was wrong with his vision.

Handed a set of crayons, Ammerine Dellenbaugh’s bright, chatty son Creede refused to use them to draw or write. Instead, he’d line them up by color, or just scribble.

As 6-year-olds, Stacey Vandell’s twins, Jake and Ryan, couldn’t remember their ABCs, didn’t know why the days were different, and couldn’t grasp the concept of time.

Over and over, these women found themselves saying the same thing to teachers and principals:

Something is not right.

But when it came to putting a label on these challenges — to getting the type of educational testing that could open the door to more appropriate schooling — they felt like they were on their own.

They hired private neuropsychologists, speech and vision experts. They spent thousands of dollars to diagnose learning disabilities they say their schools should have identified much earlier.

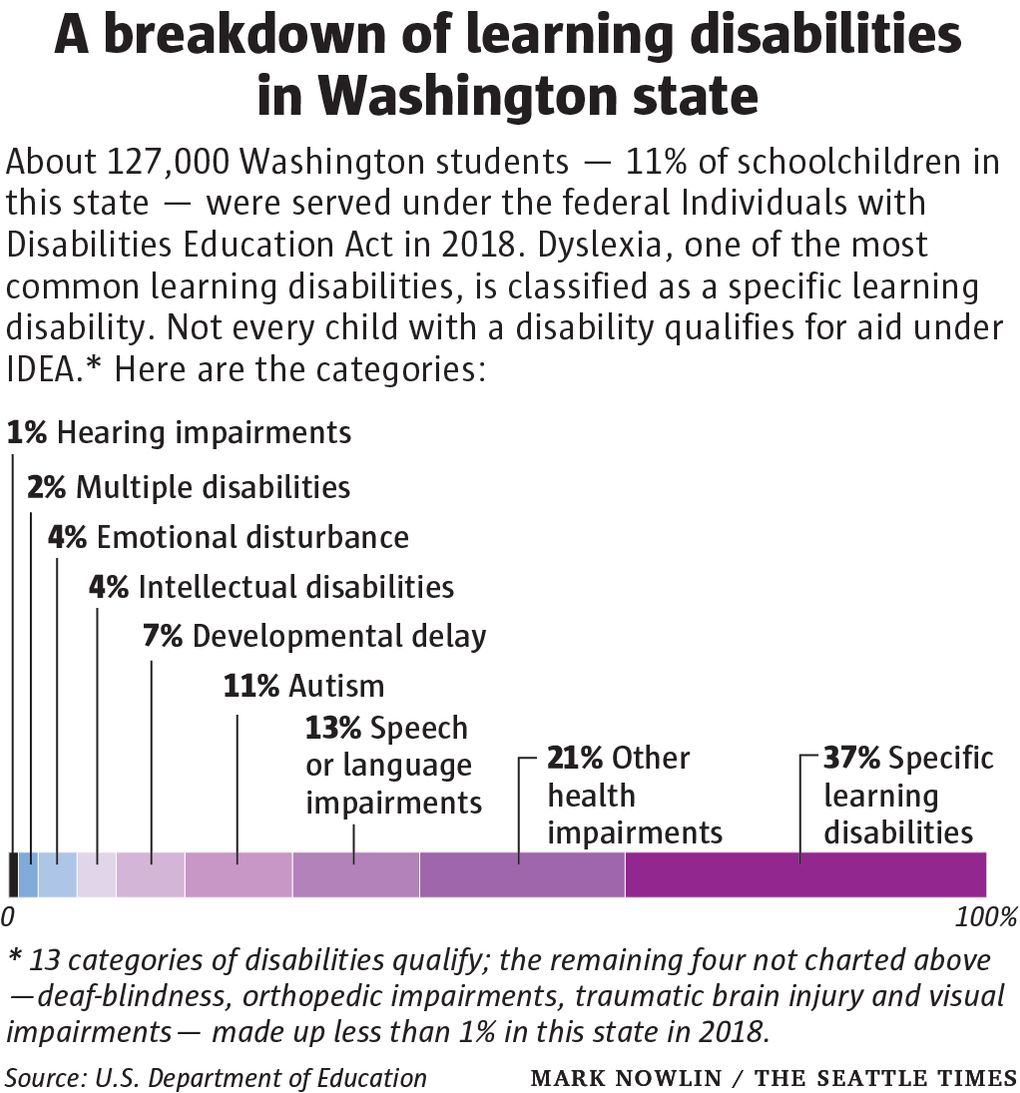

Educators have long known that dyslexia and other learning disabilities can have devastating impacts for students if not diagnosed and addressed early. In Washington, nearly 48,000 children in 2018 were identified as having a “specific learning disability,” which includes dyslexia, dyscalculia and dysgraphia. It is the most common category of learning disability.

Those numbers likely understate the problem because many children aren’t diagnosed. It’s estimated that as many as one in five children have some degree of dyslexia.

Yet most Washington districts decide if a child is eligible for services using a model that is not supported by research.

The Seattle Times spoke to dozens of parents who hit brick walls when trying to get the help they needed for their children. Their experiences point to a pervasive problem in Washington: Schools are failing children who learn differently by taking too long to address problems.

Their complaints have common themes:

- Teachers assured them their children would grow out of the problem.

- Schools were reluctant to test until students started failing, forcing many parents to pay for private testing.

- Interventions, especially for reading, were often too little and too late.

Washington ranks poorly on federal special-education reports because of its low student outcomes and segregated classrooms. It’s hard to know how much of the problem is due to a lack of diagnostic testing, but even state officials acknowledge that they’re not doing enough to identify reading problems like dyslexia, which affects as many as one in five children.

That problem is compounded by the fact that Washington — like most states — has a shortage of both special-education teachers and school psychologists. And although the Legislature boosted special-education funding by millions of dollars this year, it came up far short of what advocates wanted.

How special education works

Special education has a complex language all its own, girded by federal statutes that can feel calculated to confuse as much as help parents of children like Jayden, Creede, Jake and Ryan.

The federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) gives a child with a disability an explicit right to schooling that suits their needs, but not every child who has a disability will qualify for help. The disability has to affect educational performance, and overcoming the disability has to require specially designed instruction, said Glenna Gallo, assistant superintendent of special education for Washington’s Superintendent of Public Instruction.

The law recognizes 13 categories of disabilities. Some are caught early, often by a doctor. Others are invisible, apparent only after a child with average or above-average intellectual ability falters in the classroom; they include difficulties with reading (dyslexia), calculations (dyscalculia) and writing (dysgraphia).

Luckisha Phillips and her husband, John, assumed their school would want to investigate why Jayden couldn’t remember his ABCs or write his letters. Instead, she says, they were only interested in whether he was legally entitled to help.

That’s not surprising — that’s what the federal law requires.

Most Washington school districts identify students with these types of learning disabilities through an intellectual ability test, or IQ test. This method, known as the “discrepancy model,” measures whether there is a substantial difference between a student’s intellectual ability and scores in one or more academic areas, such as reading. In other words, a student must reach a certain level of failure before qualifying for help.

But research has debunked this method as a poor model with no basis in science, said Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu Founder of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions. Ufondu called it a “wait-to-fail” approach.

Aira Jackson, director of English language arts for the state superintendent’s office, acknowledges that research calls into question the validity of the discrepancy model.