At age six, most young children are entering first grade, but not for the extraordinary Joshua Beckford.

Living with high-functioning autism, the child prodigy from Tottenham was, at the age of six, the youngest person ever to attend the prestigious Oxford University.

But he has his father to thank for this incredible feat. At just 10 months old, Beckford’s father, Knox Daniel, discovered his son’s unique learning capability while he was sitting on his lap in front of the computer.

With the keyboard being the child’s interest, Daniel said: “I started telling [Joshua] what the letters on the keyboard were and I realized that he was remembering and could understand.”

“So, if I told him to point to a letter, he could do it… Then we moved on to colours,” Daniel added.

At the age of three, Beckford could read fluently using phonics. He learned to speak Japanese and even taught himself to touch-type on a computer before he could learn to write.

“Since the age of four, I was on my dad’s laptop and it had a body simulator where I would pull out organs,” said Beckford.

In 2011, his father was aware of a programme at Oxford University that was specific to children between the age of eight and thirteen. To challenge his son, he wrote to Oxford with the hopes of getting admission for his child even though he was younger than the age prescribed for the programme.

Fortunately, Beckford was given the chance to enroll, becoming the youngest student ever accepted. The brilliant chap took a course in philosophy and history and passed both with distinction.

Beckford was too advanced for a standard curriculum; hence he was home-schooled, according to Spectacular Magazine.

Having a keen interest in the affairs of Egypt throughout his studies, the young genius is working on a children’s book about the historic and ancient nation.

Aside from his academic prowess, Beckford serves as the face of the National Autistic Society’s Black and Minority campaign. Being one with high-functioning autism, the young child helps to highlight the challenges minority groups face in their attempt to acquire autism support and services.

Last month, the wonder child was appointed Low Income Families Education (L.I.F.E) Support Ambassador for Boys Mentoring Advocacy Network in Nigeria, Uganda, Ghana, South Africa, Kenya and the United Kingdom.

BMAN Low Income Families Education (LIFE) Support was established to create educational opportunities for children from low-income families so that they have a hope of positively contributing to a thriving society.

Beckford will further hold a live mentoring session with teenagers and his father, Daniel, will facilitate a mentoring session with parents at the Father And Son Together [FAST] initiative event in Nigeria in August 2019.

In 2017, Beckford won The Positive Role Model Award for Age at The National Diversity Awards, an event which celebrates the excellent achievements of grass-root communities that tackle the issues in today’s society.

Described as one of the most brilliant boys in the world, Beckford also designs and delivers power-point presentations on Human Anatomy at Community fund-raising events to audiences ranging from 200 to 3,000 people, according to National Diversity Awards.

For a super scholar whose brain is above most of his peers and even most adults, Beckford, according to his father, “doesn’t like children his own age and only likes teenagers and adults.”

Parenting a child with high-functioning autism comes with its own challenges, his father added.

“[Joshua] doesn’t like loud noises and always walks on his tip toes and he always eats from the same plate, using the same cutlery, and drinks from the same cup,” he said.

He is, however, proud of his son’s achievements and believes he has a bright future ahead.

“I want to save the earth. I want to change the world and change peoples’ ideas to doing the right things about earth,” Beckford once said of his future.

Complaints filed against the city Department of Education by parents of special education students have skyrocketed since 2014 — sparking a “crisis” that leaves some kids without essential service for months on end, a state-commissioned report found.

The flood of parents battling the public schools system for support is threatening to overwhelm a dispute-resolution system suffering from too few hearing officers and inadequate space to hold hearings, according to the external review obtained by THE CITY.

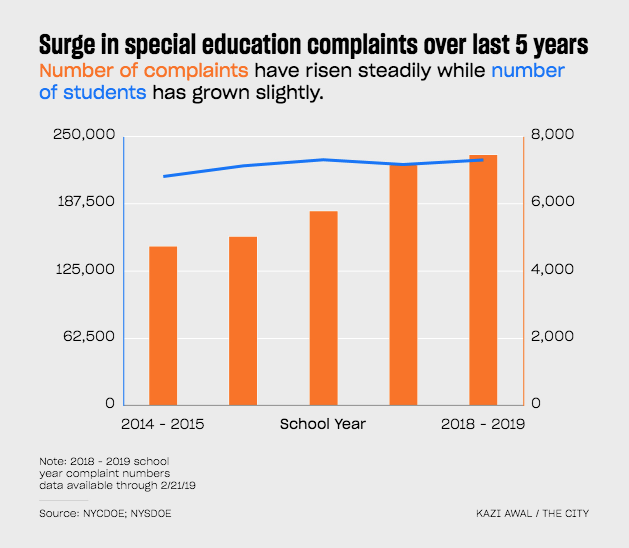

Complaints jumped 51 percent between the 2014-’15 and 2017-’18 school years, the report found. That surge has continued into the current school year, with 7,448 complaints filed as of late February — more than the total for the entire prior school year.

The average complaint was open for 202 days in 2017-’18, according to State Education Department data.

Growing complaints have caused a “crisis” that could “render an already fragile hearing system vulnerable to imminent failure and, ultimately, collapse,” Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, wrote in a 49-page report obtained through public disclosure law and provided to THE CITY.

“That it has not yet collapsed is remarkable given the staggering numbers of due process complaints filed in New York City.”

One family’s struggle

Brooklyn mom Josie Hernandez, who visited the DOE’s impartial hearing offices on Livingston Street in Brooklyn last week, said she’s been fighting to get her now 14-year-old son the services required under his individual education plan — known as an IEP — since October 2017.

The legally binding document says her son should be in a classroom capped at 12 students, and receiving speech therapy and counseling. But Hernandez says her son has never gotten all three of those requirements at any of the four schools he’s attended.

A recent neuropsych examination determined the teen is three or four grade levels behind, according to Hernandez.

“For three years, they’ve not been giving him the services mandated on the IEP,” she said. “Right now, he’s in a class with 19 kids.”

Rebecca Shore, director of litigation for the group Advocates for Children of New York, said parents file complaints for a host of reasons.

Some students are placed into schools that don’t offer programs mandated on their education plans. Others are thrust into classroom settings that don’t match those mandated by the IEP. In some cases, services called for in the IEP simply are not provided.

“When the parents come to us, unfortunately, usually it’s at a point where it’s been three or four or five or six years [without services],” said Shore, whose group provided the external review to THE CITY.

“At that point, the student needs a lot of compensatory services to make up for the lack of instruction and appropriate instruction the student experienced for that much time.”

Tuition reimbursement cases eyed

The report doesn’t attempt to identify why complaints are up. But it notes that some in the education field attribute the hike to a boost in parents using the due process system to seek tuition reimbursement for placing kids in private schools. That happens when the public school system can’t accommodate a student’s needs.

The number of students receiving reimbursement for private school tuition grew from 3,329 during the 2013-’14 school year to 4,431 in 2016-’17, according to the DOE.

The agency attributed the vast majority of complaint filings to tuition-reimbursement requests. Not all of those private school placements resulted, though, from due process complaints.

The DOE’s spending on the most common type of private school placement — known as Carter Cases — nearly doubled from $222 million to $417 million between the 2013 and 2016 school years, according to City Council budget documents.

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in June 2014 that the city wouldn’t be as litigious as the prior administration in dealing with parent tuition-reimbursement requests. The requests hit a high in the 2016-’17 school year, the latest figures supplied by the DOE show.

The de Blasio plan called for an expedited process for a majority of those cases, in which the city would decide within 15 days whether to settle. But advocates say the much-heralded policy sparked a volume of filings that overwhelmed city workers and made the 15-day deadline impossible to meet.

“A significant amount of time has been spent trying to get these cases to settlement, so that process can sometimes take six to eight months itself,” said Nelson Mar, a senior staff attorney at Bronx Legal Services.

He noted the root of the problem is that public schools simply don’t have enough services to cover the needs of many of the city’s 224,000 special education students.

New York City logged more due process complaints than California, Florida, Texas and Pennsylvania combined, according to 2016-’17 data collected by the state Education Department.

“The reason why you’re seeing these astronomical numbers is because they have never addressed the fundamental problems with their delivery of special education services,” said Mar. “There’s not enough programs and not enough staff to provide services.”

City works on changes

While the external review was completed in February, the State Education Department didn’t release it publicly and instead included it as an appendix to a “Compliance Assurance Plan” produced by state officials earlier this month.

That plan detailed how New York City was out of compliance with federal law for the 13th straight year on its delivery of services for special education students. Among the issues raised: mandated services on student IEPs not being provided.

One of the reasons the complaint process moves so slowly in New York City is because the DOE isn’t trying to resolve enough cases through mediation, the plan noted. There were only 126 mediations held last year, according to state data.

The compliance report highlighted a number of other failings within the complaint system — which is run by the city but overseen by the state. One issue: 122 hearings are scheduled per day on average and there are only 10 hearing rooms.

And the hearing offices are all in downtown Brooklyn, an inconvenient location for many parents, the state plan noted. Plus, parents have to navigate through a connected lunchroom that doubles as a space for teachers who have been reassigned after being accused of misconduct.

State officials gave city education officials until June 3 to file a corrective action plan, which must include boosting the number of staffers at the impartial hearing office and adding hearing rooms.

City officials said they’re already implementing many of the requirements, while they’ve asked the state to certify more hearing officers.

“We’re committed to improving the impartial hearing process for families, and we’re hiring more impartial hearing staff and investing an additional $3.4 million to add impartial hearing rooms and make physical improvements to the impartial hearing office,” said Danielle Filson, a DOE spokesperson. “We’re also hiring more attorneys to reduce case backlog as part of a larger $33 million investment in special education, and we’re supporting the state as much as possible to hire more hearing officers.”

DOE officials said they’ve already moved the reassigned teachers from the lunchroom.

State officials said they’ve been pleased with city Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza’s actions on special education thus far.

“We are encouraged by Chancellor Carranza’s commitment to make the systemic changes necessary to transform the way New York City supports students with disabilities and we have already started to see improvements,” said state DOE spokesperson Emily DeSantis.

It’s that time of the year again Beautiful Minds families…Summertime! Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu lends us his recommendations for this year’s best and most fun summer camps for 2019. Summer camp can be a fun and exciting experience for children and adults with autism. Families can search for accredited summer camps on the American Camp Association website – they have thousands of listings, and there is an option to specify that you are looking for a camp serving children or young adults with autism.

Beautiful Minds Inc. is committed to promoting inclusion of children and adults with autism across all programs and organizations for families. Leading the Way: Autism-Friendly Youth Organizations is a guide to help organizations learn to integrate youth with autism into existing programs, communicate with parents, and train their staff. Please feel free to share this guide with any camps, sports programs, or other youth organizations your son might be interested in.

If you are looking for funding or financial assistance, many camps will offer tuition/fees on a sliding scale relative to your income. You can also find Family Grant Opportunities on our website.

Another option to consider is requesting an Extended School Year (ESY) program through your child’s school district or at the next IEP meeting. If there is evidence that a child experiences a substantial regression in skills during school vacations, he/she may be entitled to ESY services. These services would be provided over long breaks from school (summer vacation) to prevent substantial regression. This is usually discussed during annual IEP reviews but if you are concerned about regression, now is the best time to bring it up with your child’s team at school. Some children attend the camps listed in our Resource Guide as part of their Extended School Year (ESY) program.

Another good resource is MyAutismTeam, a social network specifically for parents of individuals with autism. Join more than 40,000 parents from all parts of the country and find parents whose children are similar to yours or who live near you, get tips and support, ask questions, and exchange referrals on great providers, services, and camps for your child.

Families can also reach out to the state’s Parent Training and Information Center to find additional information and support in their local areas.

Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu’s Top 5 Things to Know About Racial and Cultural Disparities in Special Education

By: Dr Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D.

Each year, roughly 6 million students with disabilities, ages 6 to 21, receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Although special education is a source of critical services and supports for these students, students of color with disabilities still face a number of obstacles impeding their ability to succeed in school. According to Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D., Educational Psychologist and founder of Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, “In 2017, only 4 percent of black and Hispanic 12th -grade students with disabilities achieved proficiency in reading, while practically none of those students achieved proficiency in math or science. This is where the problem begin!”

In late December 2017, the U.S. Department of Education issued final rules to prompt states to proactively address racial and ethnic disparities in the identification, placement, and discipline of children with disabilities. That same month, they released comprehensive legal guidance describing schools’ obligations under federal civil rights and disabilities studies not to discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin in the administration of special education. To help educators, school communities, and education officials understand the challenges prompting these initiatives, here are Dr. Ufondu’s five critical facts about racial and ethnic disparities in special education:

There are wide disparities in disability identification by race and ethnicity.

In general, students of color are disproportionately overrepresentedamong children with disabilities: black students are 40 percent more likely, and American Indian students are 70 percent more likely, to be identified as having disabilities than are their peers. The overrepresentation of particular demographics varies depending on the type of disability, and disparities are particularly prevalent for so-called high-incidence disabilities, including specific learning disabilities and intellectual disabilities. Black students are twice as likely to be identified as having emotional disturbance and intellectual disability as their peers. American Indian students are twice as likely to be identified as having specific learning disabilities, and four times as likely to be identified as having developmental delays. Research does not support the conclusion that race and cultural disproportionality in special education is due to differences in socioeconomic status between groups. Efforts to reduce disparity, then, should support more widespread screening for developmental delays among young children, and should assist educators in identifying disabilities early and appropriately to address student needs. One study found that 4-year-old black children were also disproportionately underrepresented in early childhood special education and early intervention programs.

Many children of color with disabilities experience a segregated education system.

While children with disabilities have been placed in more inclusive education settings since the early 1990s, progress toward inclusion has not improved over the last decade, specifically. To ensure greatest access to rigorous academic content, IDEA statute requires that children with disabilities receive their education in the least restrictive environment, alongside children without disabilities to the maximum extent appropriate. However, in 2014, children of color with disabilities—including 17 percent of black students, and 21 percent of Asian students—were placed in the regular classroom, on average, less than 40 percent of the school day. By comparison, 11 percent of white and American Indian or Alaskan Native children with disabilities were similarly placed.

In a single year, 1 in 5 black, American Indian, and multiracial boys with disabilities were suspended from school.

According to the U.S. Department of Education’s 2013 to 2014 Civil Rights Data Collection, students with disabilities (12 percent) are twice as likely as their peers without disabilities (5 percent) to receive at least one out-of-school suspension. Suspension from school is associated with an increased risk of dropout, grade retention, and contact with the juvenile justice system. To ensure students’ access to a free and appropriate public education, as promised by IDEA, schools should take care to address both academic and behavioral needs in the development of students’ individualized education programs (IEPs).

IDEA provisions intended to address racial and ethnic disparities are underused.

For example, Section 618(d) of IDEA requires states to identify school districts with significant disproportionality, by race or ethnicity, in the identification, placement, or discipline of children with disabilities. Such school districts must reserve 15 percent of federal funds provided under IDEA, Part B to implement comprehensive, coordinated early intervening services to address the disparity. However, according to the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Government Accountability Office, each year, 3 percent or less of all school districts are identified as having significant disproportionality. In 2013, 75 percent of the identified school districts were located in seven states. That same year, 22 states did not identify any districtswith significant disproportionality. While there is no consensus definition of significant disproportionality – as the term refers to an IDEA legal standard, to be decided on by states, the U.S. Department of Education published preliminary data identifying extensive racial and ethnic disparities in every state in the union. Under the new final rule from the U.S. Department of Education, all states will be required to follow a standard approach to define and identify significant disproportionality in school districts.

Greater flexibility to implement comprehensive, coordinated early intervening services (CEIS) may help school districts address special education disparities, and improve academic outcomes for children of color with disabilities.

Historically, school districts with significant disproportionality were prohibited from using comprehensive CEIS to address the needs of preschool children or children with disabilities. Such restrictions would have prevented schools from using comprehensive CEIS for training IEP teams to build better behavioral supports into students’ IEPs, even to address placement or discipline disparities. Such restrictions would also have prevented efforts to identify and serve preschool children in order to prevent future disparities in disability identification. Under the new final rule, school districts may implement comprehensive CEIS in a manner that addresses identified racial and ethnic disparities, which may include activities that support students with disabilities and preschool children.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D.

A worried mother says, “There’s so much publicity about the best programs for teaching kids to read. But my daughter has a learning disability and really struggles with reading. Will those programs help her? I can’t bear to watch her to fall further behind.”

Fortunately, in recent years, several excellent, well-publicized research studies (including the Report of the National Reading Panel) have helped parents and educators understand the most effective guidelines for teaching all children to read. But, to date, the general public has heard little about research on effective reading interventions for children who have learning disabilities (LD). Until now, that is!

This article will describe the findings of a research study that will help you become a wise consumer of reading programs for kids with reading disabilities.

Research reveals the best approach to teaching kids with LD to read

You’ll be glad to know that, over the past 30 years, a great deal of research has been done to identify the most effective reading interventions for students with learning disabilities who struggle with word recognition and/or reading comprehension skills. Between 1996 and 1998, a group of researchers led by H. Lee Swanson, Ph.D., Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of California at Riverside, set out to synthesize (via meta-analysis) the results of 92 such research studies (all of them scientifically-based). Through that analysis, Dr. Swanson identified the specific teaching methods and instruction components that proved most effective for increasing word recognition and reading comprehension skills in children and teens with LD.

Some of the findings that emerged from the meta-analysis were surprising. For example, Dr. Swanson points out, “Traditionally, one-on-one reading instruction has been considered optimal for students with LD. Yet we found that students with LD who received reading instruction in small groups (e.g., in a resource room) experienced a greater increase in skills than did students who had individual instruction.”

In this article, we’ll summarize and explain Dr. Swanson’s research findings. Then, for those of you whose kids have LD related to reading, we’ll offer practical tips for using the research findings to “size up” a particular reading program. Let’s start by looking at what the research uncovered.

A strong instructional core

Dr. Swanson points out that, according to previous research reviews, sound instructional practices include: daily reviews, statements of an instructional objective, teacher presentations of new material, guided practice, independent practice, and formative evaluations (i.e., testing to ensure the child has mastered the material). These practices are at the heart of any good reading intervention program and are reflected in several of the instructional components mentioned in this article.

Improving Word Recognition Skills: What Works?

“The most important outcome of teaching word recognition,” Dr. Swanson emphasizes, “is that students learn to recognize real words, not simply sound out ‘nonsense’ words using phonics skills.”

What other terms might teachers or other professionals use to describe a child’s problem with “word recognition”

- decoding

- phonics

- phonemic awareness

- word attack skills

Direct instruction appears the most effective approach for improving word recognition skills in students with learning disabilities. Direct instruction refers to teaching skills in an explicit, direct fashion. It involves drill/repetition/practice and can be delivered to one child or to a small group of students at the same time.

The three instruction components that proved most effective in increasing word recognition skills in students with learning disabilities are described below. Ideally, a reading program for word recognition will include all three components.

Increasing Word Recognition Skills in Students With LD

| Instruction component | Program Activities and Techniques* |

|---|---|

| Sequencing | The teacher:

|

| Segmentation | The teacher:

|

| Advanced organizers | The teacher:

|

* May be called “treatment description” in research studies.

Improving reading comprehension skills: What works?

The most effective approach to improving reading comprehension in students with learning disabilities appears to be a combination of direct instruction and strategy instruction. Strategy instruction means teaching students a plan (or strategy) to search for patterns in words and to identify key passages (paragraph or page) and the main idea in each. Once a student learns certain strategies, he can generalize them to other reading comprehension tasks. The instruction components found most effective for improving reading comprehension skills in students with LD are shown in the table below. Ideally, a program to improve reading comprehension should include all the components shown.

Improving Reading Comprehension in Students With LD

| Instruction component | Program Activities and Techniques* |

|---|---|

| Directed response/questioning | The teacher:

The teacher and student(s):

|

| Control difficulty of processing demands of task | The teacher:

The activities:

|

| Elaboration | The activities:

|

| Modeling of steps by the teacher | Teacher demonstrates the processes and/or steps the students are to follow. |

| Group instruction | Instruction and/or verbal interaction takes place in a small group composed of students and teacher |

| Strategy cues | The teacher:

The activities:

|

* May be called “treatment description” in research studies.

Evaluating your child’s reading program

Now you are well-equipped with research-based guidelines on the best teaching methods for kids with reading disabilities. At Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, we provide guidelines that will serve you well, even as new reading programs become available. To evaluate the reading program used in your child’s classroom, Beautiful Minds inc. founder, Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu recommends you follow these steps:

- Ask for detailed literature on your child’s reading program. Some schools voluntarily provide information about the reading programs they use. If they don’t do this — or if you need more detail than what they provide — don’t hesitate to request it from your child’s teacher, special education teacher, resource specialist, or a school district administrator. In any school — whether public or private — it is your right to have access to such information.

- Once you have literature on a specific reading program, locate the section(s) that describe its instruction components. Take note of where your child’s reading program “matches” and where it “misses” the instruction components recommended in this article. To document what you find, you may find our worksheets helpful.

- Find out if the instruction model your child’s teacher uses is Direct Instruction, Strategy Instruction, or a combination approach. Some program literature states which approach a teacher should use; in other cases, it’s up to the teacher to decide. Compare the approach used to what this article describes as being most effective for addressing your child’s area of need.

- Once you’ve evaluated your child’s reading program, you may feel satisfied that her needs are being met. If not, schedule a conference with her teacher (or her IEP team, if she has one) to present your concerns and discuss alternative solutions.

Hope and hard work — not miracles

Finally, Dr. Swanson cautions, “There is no ‘miracle cure’ for reading disabilities. Even a reading program that has all the right elements requires both student and teacher to be persistent and work steadily toward reading proficiency.”

But knowledge is power, and the findings of Dr. Swanson’s study offer parents and teachers a tremendous opportunity to evaluate and select reading interventions most likely to move kids with LD toward reading success.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D

The school bell may stop ringing, but summer is a great time for all kinds of educational opportunities. Children with learning disabilities particularly profit from learning activities that are part of their summer experience — both the fun they have and the work they do.

Beautiful Minds Inc. found Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D. has packed this virtual Beach Bag of activities for teachers to help families get ready for summer and to launch students to a fun, enriching summer.

In the virtual Beach Bag you’ll find materials you can download and distribute, but you’ll also find ideas for things that you may want to gather and offer to students and parents and for connections you’ll want to make to help ensure summer learning gain rather than loss.

– Put an article on strategies for summer reading for children with dyslexia in your school or PTA newsletter. Send it home with your students to the parents.

If many of your students go to summer camp, send the parents When the Child with Special Needs goes off to Summer Camp an article by Rick Lavoie which tells parents what to do to support their children during camp.

– Teach them an important skill they can use over the summer. Read Teaching Time Management to Students with Learning Disabilities to learn about task analysis, which families can use to plan summer projects.

– Make sure your students are able to read over the summer — put books into children’s hands. Register with First Book and gain access to award-winning new books for free and to deeply discounted new books and educational materials.

– Tell your parents about Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, which allows their children to listen to books over the summer.

– Encourage writing. Send The Writing Road home to your parents so they can help their children. Give each of your students a stamped, addressed postcard so they can write to you about their summer adventures.

– Get your local public library to sign kids up for summer reading before school is out. Invite or ask your school librarian to coordinate a visit from the children’s librarian at the public library near the end of the school year. Ask them to talk about summer activities, audio books, and resources from the National Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Have them talk about summer activities at the library and distribute summer reading program materials.

– Study reading incentive programs by publishers and booksellers such as Scholastic’s Summer Reading Buzz, HarperCollins Children’s Books Reading Warriors, or the Barnes & Noble Summer Reading Program. If you think these programs will motivate your students, let the families know about them. Find ways to make accommodations so they can participate if necessary.

– Offer recommended reading. LD OnLine’s Kidzone lists books that are fun summertime reads. The Association for Library Services to Children, a division of the American Library Association, offers lists for summer reading. Or ask your school or public librarian for an age-appropriate reading list.

– Encourage your parents to set up a summer listening program which encourages their children to listen to written language. Research shows that some children with learning disabilities profit from reading the text and listening to it at the same time.

– Offer recommendations for active learning experiences. Check with your local department of parks and recreation about camps and other activities. Find out what exhibits, events, or concerts are happening in your town over the summer. Encourage one of your parents to organize families of children with learning disabilities together for learning experiences.

Dr. Ufondu also desires for parents to plan ahead. Work with the teachers a grade level above to develop a short list of what students have to look forward to when they return to school in the fall. Many kids with learning disabilities will want to study over the summer so that they can get a head start.

By: Ifeanyi-Allah Ufondu, Marie Tejero Hughes, Sally Watson Moody, and Batya Elbaum

After discussion of each grouping format, implications for practice are highlighted with particular emphasis on instructional practices that promote effective grouping to meet the needs of all students during reading in general education classrooms. In the last 5 years, two issues in education have assumed considerable importance: reading instruction and inclusion. With respect to reading instruction, the issue has been twofold: (a) Too many students are not making adequate progress in reading), and (b) we are not taking advantage of research based practices in the implementation of reading programs. In the popular press the complexities and subtleties of this issue have been reduced to a simple argument between phonics versus whole language, but the reality is that there is considerable concern about the quality and effectiveness of early reading instruction. With respect to the second major issue of inclusion, considerable effort has been expended to restructure special and general education so that the needs of students with disabilities are better met within integrated settings. The result is that more students with disabilities receive education within general education settings than ever before, and increased collaboration is taking place between general and special education.

Both of these issues-reading instruction and inclusion-have been the topics for national agendas (e.g., President Clinton’s announcement in his State of the Union Address in 1996 that every child read by the end of third grade, Regular Education Initiative), state initiatives (e.g., Texas and California Reading Initiatives), and local school districts. The implementation of practices related to both of these issues has immediate and substantive impact on professional development, teaching practices, and materials used by classroom teachers.

Grouping practices for reading instruction play a critical role in facilitating effective implementation of both reading instruction and inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classes. Maheady referred to grouping as one of the alterable instructional factors that “can powerfully influence positively or negatively the levels of individual student engagement and hence academic progress”, as well as a means by which we can address diversity in classrooms. As increased numbers of students with learning disabilities (LD) are receiving education in the general education classroom, teachers will need to consider grouping practices that are effective for meeting these students’ needs. Furthermore, reading instruction is the academic area of greatest need for students with LD; thus, grouping practices that enhance the reading acquisition skills of students with LD need to be identified and implemented.

Until relatively recently, most teachers used homogeneous (same ability) groups for reading instruction. This prevailing practice was criticized based on several factors; ability grouping: (a) lowers self-esteem and reduces motivation among poor readers, (b) restricts friendship choices, and (c) widens the gap between poor readers and good readers. Perhaps the most alarming aspect of ability grouping was the finding that students who were the poorest readers received reading instruction that was inferior to that of higher ability counterparts in terms of instructional time; time reading, discussing, and comprehending text (Allington, 1980); and appropriateness of reading materials. As a result, heterogeneous grouping practices now prevail, and alternative grouping practices such as cooperative learning and peer tutoring have been developed.

As general education classrooms become more heterogeneous, due in part to the integration of students with LD, both special and general education teachers need to have at their disposal a variety of instructional techniques designed to meet the individual needs of their students. In this article, we provide an overview of the recent research on grouping. practices (whole class, small group, pairs, one-on-one) teachers use during reading instruction; furthermore, implications for reading instruction are highlighted after each discussion.

Whole-class instruction

Research findings

Considerable research has focused on the fact that for much of general education the instructional format is one in which the teacher delivers education to the class as a whole. The practice of whole-class instruction as the dominant approach to instruction has been well documented. For example, in a study that involved 60 elementary, middle, and high school general education classrooms that were observed over an entire year, whole-class instruction was the norm. When teachers were not providing whole-class instruction, they typically circulated around the room monitoring progress and behavior or attended to their own paperwork.

Elementary students have also reported that whole-class instruction is the predominant instructional grouping format. Students noted that teachers most frequently provided reading instruction to the class as a whole or by having students work alone. Students less frequently reported opportunities to work in small groups, and they rarely worked in pairs. Although students preferred to receive reading instruction in mixed-ability groups, they considered same ability grouping for reading important for nonreaders. Students who were identified as better readers revealed that they were sensitive to the needs of lower readers and did not express concerns about the unfairness of having to help them in mixed-ability groups. In particular, students with LD expressed appreciation for mixed-ability groups because they could then readily obtain help in identifying words or understanding what they were reading.

Many professionals have argued that teachers must decentralize some of their instruction if they are going to appropriately meet the needs of the increasing number of students with reading difficulties. However, general education teachers perceive that it is a lot more feasible to provide large-group instruction than small-group instruction for students with LD in the general education classroom. The issue is also true for individualizing instruction or finding time to provide mini lessons for students with LD. Teachers have reported that these are difficult tasks to embed in their instructional routines.

Implications for practice

Numerous routines and instructional practices can contribute to teachers’ effective use of whole-class instruction and implementation of alternative grouping practices.

Teachers can involve all students during whole-class instruction by asking questions and then asking students to partner to discuss the answer. Ask one student from the pair to provide the answer. This keeps all students engaged.

Teachers can use informal member checks to determine whether students agree, disagree, or have a question about a point made. This allows each student to quickly register a vote and requires students to attend to the question asked. Member checks can be used frequently and quickly to maintain engagement and learning for all students.

Teachers can ask students to provide summaries of the main points of a presentation through a discussion or after directions are provided. All students benefit when the material is reviewed, and a student summary allows the teacher to determine whether students understand the critical features.

Because many students with LD are reluctant to ask questions in large groups, teachers can provide cues to encourage and support students in taking risks. For example, teachers can encourage students to ask a “who,” “what,” or “where” question.

At the conclusion of a reading lesson, the teacher can distribute lesson reminder sheets, which all the students complete. These can be used by teachers to determine (a) what students have learned from the lesson, (b) what students liked about what they learned, and (c) what else students know about the topic.

Small-group instruction

Research findings

Small-group instruction offers an environment for teachers to provide students extensive opportunities to express what they know and receive feedback from other students and the teacher. Instructional conversations are easier to conduct and support with a small group of students. In a recent meta-analysis of the extent to which variation in effect sizes for reading outcomes for students with disabilities was associated with grouping format for reading instruction, small groups were found to yield the highest effect sizes. It is important to add that the overall number of small-group studies available in the sample was two. However, this finding is bolstered by the results of a meta-analysis of small-group instruction for students without disabilities, which yielded significantly high effect sizes for small-group instruction. The findings from this meta-analysis reveal that students in small groups in the classroom learned significantly more than students who were not instructed in small groups.

In a summary of the literature across academic areas for students with mild to severe disabilities, Polloway, Cronin, and Patton indicated that the research supported the efficacy of small-group instruction. In fact, their synthesis revealed that one-to-one instruction was not superior to small-group instruction. They further identified several benefits of small-group instruction, which include more efficient use of teacher and student time, lower cost, increased instructional time, increased peer interaction, and opportunities for students to improve generalization of skills.

In a descriptive study of the teacher-student ratios in special education classrooms (e.g., 1-1 instruction, 1-3 instruction, and 1-6 instruction), smaller teacher-led groups were associated with qualitatively and quantitatively better instruction. Missing from this study was an examination of student academic performance; thus, the effectiveness of various group sizes in terms of student achievement could not be determined.

A question that requires further attention regarding the effectiveness of small groups is the size of the group needed based on the instructional needs of the student. For example, are reading group sizes of six as effective as groups of three? At what point is the group size so large that the effects are similar to those of whole-class instruction? Do students who are beginning readers or those who have struggled extensively learning to read require much smaller groups, perhaps even one-on-one instruction, to ensure progress?

Although small group instruction is likely a very powerful tool to enhance the reading success of many children with LD, it is unlikely to be sufficient for many students. In addition to the size of the group, issues about the role of the teacher in small-group instruction require further investigation. In our analysis of the effectiveness of grouping practices for reading, each of the two studies represented different roles for the teacher. In one study, the teacher served primarily as the facilitator, while in a second study the teacher’s role was primarily one of providing direct instruction. Although the effect sizes for both studies were quite high (1.61 and .75, respectively), further research is needed to better understand issues related to a teacher’s role and responsibility within the group.

Implications for practice

Many teachers reveal that they have received little or no professional development in how to develop and implement successful instructional groups. Effective use of instructional groups may be enhanced through some of the following practices.

Perhaps the most obvious, but not always the most feasible application of instructional groups, is to implement reading groups that are led by the teacher. Whereas these groups have been demonstrated as effective, many teachers find it difficult to provide effective instruction to other members of the class while they are providing small-group instruction. Some teachers address this problem by providing learning centers, project learning, and shared reading time during small group instruction.

Flexible grouping has also been suggested as a procedure for implementing small-group instruction that addresses the specific needs of students without restricting their engagement to the same group all the time. Flexible grouping is considered an effective practice for enhancing the knowledge and skills of students without the negative social consequences associated with more permanent reading groups. This way teachers can use a variety of grouping formats at different times, determined by such criteria as students’ skills, prior knowledge, or interest. Flexible groups may be particularly valuable for students with LD who require explicit, intensive instruction in reading as well as opportunities for collaborative group work with classmates who are more proficient readers. Flexible grouping may also satisfy students’ preferences for working with a range of classmates rather than with the same students all of the time.

Student-led small groups have become increasingly popular based on the effective implementation of reciprocal teaching. This procedure allows students to take turns assuming the role of the leader and guiding reading instruction through question direction and answer facilitation.

Peer pairing and tutoring

Research findings

Asking students to work with a peer is an effective procedure for enhancing student learning in reading and is practical to implement because teachers are not responsible for direct contact with students. For students with LD involved in reading activities, the overall effect size for peer pairing based on a meta-analysis was ES = .37. This finding was similar to one reported for students with LD (ES = .36; Mathes & Fuchs, 1994) and for general education students (mean ES = .40).

The Elbaum and colleagues report revealed that the magnitude of the effects for peer pairing differed considerably depending on the role of the student within the pair. For example, when students with disabilities were paired with same-age partners, they derived greater benefit (ES = .43) from being tutored rather than from engagement in reciprocal tutoring (ES = .15). This may be a result that for the most part the tutors were students without disabilities who demonstrated better reading skills and were able to provide more effective instruction. These findings differ, however, when the peer pairing is cross-age rather than same-age. Overall, cross-age peer pairing students with disabilities derived greater benefit when they served in the role of tutor.

Students with LD prefer to work in pairs (with another student) rather than in large groups or by themselves. In fact, many students with LD consider other students to be their favorite teacher. Considering the high motivation students express for working with peers and the moderately high effect sizes that result from peer pairing activities for reading, it is unfortunate that students report very low use of peer pairing as an instructional procedure.

Implications for practice

Because students appreciate and benefit from opportunities to work with peers in reading activities, the following instructional practices may enhance opportunities for teachers to construct effective peer pairing within their classrooms.

Classwide Peer Tutoring (CWPT) is an instructional practice developed at Juniper Gardens to “increase the proportion of instructional time that all students engage in academic behaviors and provide pacing, feedback, immediate error correction, high mastery levels, and content coverage”. CWPT requires 30 minutes of instructional time during which 10 minutes is planned for each student to serve as a tutor, 10 minutes to be tutored, and 5 to 10 minutes to add and post individual and team points. Tutees begin by reading a brief passage from their book to their tutor, who in turns provides immediate error correction as well as points for correctly reading the sentences. When CWPT is used for reading comprehension, the tutee responds to “who, what, when, where, and why” questions provided by the tutor concerning the reading passage. The tutor corrects responses and provides the tutee with feedback.

Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS) borrows the basic structure of the original CWPT but expands the procedures to engage students in strategic reading activities. Students are engaged in three strategic reading activities more typically addressed during teacher directed instruction: partner reading with retell, paragraph summary, and prediction relay. PALS provides students with intensive, systematic practice in reading aloud, reviewing and sequencing information read, summarizing, stating main ideas, and predicting.

Think-Pair-Share hare was described by McTighe and Lyman as a procedure for enhancing student engagement and learning by providing students with opportunities to work individually and then to share their thinking or work with a partner. First, students are asked to think individually about a topic for several minutes. Then they are asked to work with a partner to discuss their thinking or ideas and to form a joint response. Pairs of students then share their responses with the class as a whole.

One-on-one instruction

Research findings

Traditionally, one-on-one instruction in which the student receives explicit instruction by the teacher is considered the most effective practice for enhancing outcomes for students with LD. In fact, the clinical model where the teacher works directly with the student for a designated period of time has a long standing tradition in LD. Most professionals consider one-on-one instruction to be the preferred procedure for enhancing outcomes in reading . Many professionals perceive one-on-one instruction as essential for students who are falling to learn to read: “Instruction in small groups may be effective as a classroom strategy, but it is not sufficient as a preventive or remedial strategy to give students a chance to catch up with their age mates”.

In a review of five programs designed for one-on-one instruction, Wasik and Slavin revealed that all of the programs were highly effective, even though they represented a broad range of methodologies. Though one-on-one instructional procedures are viewed as highly effective, they are actually infrequently implemented with students with LD, and when implemented, it is often for only a few minutes.

In a recent review of research on one-on-one instruction in reading, no published studies were identified that compared one-on-one instruction with other grouping formats (e.g., pairs, small groups, whole class) for elementary students with LD. Thus, though one-on-one instruction is a highly prized instructional procedure for students with LD, very little is known about its effectiveness.

Implications for practice

The implications for practice of one-on-one instruction are in many ways the most difficult to define because although there is universal agreement on its value, very little is known about its effectiveness for students with LD relative to other grouping formats. Furthermore, the instructional implications for practitioners revolve mostly around assisting them in restructuring their classrooms and caseloads so that it is possible for them to implement one-on-one instruction. Over the past 8 years we have worked with numerous special educators who have consistently informed us that the following factors impede their ability to implement one-on-one instruction: (a) case loads that often require them to provide services for as many as 20 students for 2 hours per day, forcing group sizes that exceed what many teachers perceive as effective; (b) increased requirements to work collaboratively with classroom teachers, which reduces their time for providing instruction directly to students; and (c) ongoing and time-consuming paperwork that facilitates documentation of services but impedes implementation of services.

Considering the “reality factors” identified by teachers, it is difficult to imagine how they might provide the one-on-one instruction required by many students with LD in order to make adequate progress in reading. Certainly, it would require restructuring special education so that the number of students receiving services and the amount of time these services are provided by special education teachers is altered.

Research studies have repeatedly shown that reading instruction in many classrooms is not designed to provide students with sufficient engaged reading opportunities to promote reading growth. We have provided a summary of recent research on the effectiveness for students with LD of various grouping practices that can increase engaged reading opportunities, as well as implications of this research for classroom instruction. As classrooms become more diverse, teachers need to vary their grouping practices during reading instruction. There needs to be a balance across grouping practices, not a sweeping abandonment of smaller grouping practices in favor of whole-class instruction. Teachers can meet the needs of all students, including the students with LD, by careful use of a variety of grouping practices, including whole-class instruction, teacher- and peer-led small group instruction, pairing and peer tutoring, and one-on-one instruction.

About the authors

Ifeanyi-Allah Ufondu, PhD, is the Nation’s leading Special Needs advocate and Educational Psychologist. He is also the founder of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions. His current interests include best grouping practices for reading instruction and advocacy for At-Risk youth. Marie Tejero Hughes, PhD, is a research assistant professor in the School of Education at the University of Miami. Her research interests include parental involvement and instructional strategies for students with disabilities in inclusive settings. Sally Watson Moody is a senior research associate in the School of Education at the University of Miami. Her research interests include instructional grouping and effective reading instruction for students with learning disabilities. Batya Elbaum, PhD, is an assistant research professor in the School of Education at the University of Miami. Her primary research is on the academic progress and social development of students with learning disabilities.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi A. Ufondu, Founder

Along with new smiling faces, a new school year brings special education teachers new IEPs, new co-teaching arrangements, new assessments to give, and more. In order to help you be as effective as you can with your new students, we’ve put together our top 10 list of back-to-school tips that we hope will make managing your special education program a little easier.

1. Organize all that paperwork

Special educators handle lots of paperwork and documentation throughout the year. Try to set up two separate folders or binders for each child on your case load: one for keeping track of student work and assessment data and the other for keeping track of all other special education documentation.

2. Start a communication log

Keeping track of all phone calls, e-mails, notes home, meetings, and conferences is important. Create a “communication log” for yourself in a notebook that is easily accessible. Be sure to note the dates, times, and nature of the communications you have.

3. Review your students’ IEPs

The IEP is the cornerstone of every child’s educational program, so it’s important that you have a clear understanding of each IEP you’re responsible for. Make sure all IEPs are in compliance (e.g., all signatures are there and dates are aligned). Note any upcoming IEP meetings, reevaluations, or other key dates, and mark your calendar now. Most importantly, get a feel for where your students are and what they need by carefully reviewing the present levels of performance, services, and modifications in the IEP.

4. Establish a daily schedule for you and your students

Whether you’re a resource teacher or self-contained teacher, it’s important to establish your daily schedule. Be sure to consider the service hours required for each of your students, any related services, and co-teaching. Check your schedule against the IEPs to make sure that all services are met. And keep in mind that this schedule will most likely change during the year!

5. Call your students’ families

Take the time to introduce yourself with a brief phone call before school starts. You’ll be working with these students and their families for at least the next school year, and a simple “hello” from their future teacher can ease some of the back-to-school jitters!

6. Touch base with related service providers

It’s important to contact the related service providers — occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech/language therapists, or counselors — in your school as soon as possible to establish a schedule of times for your students who need these services. The earlier you touch base, the more likely you’ll be able to find times that work for everyone.

7. Meet with your general education co-teachers

Communicating with your general education co-teachers will be important throughout the year, so get a head start on establishing this important relationship now! Share all of the information you can about schedules, students, and IEP services so that you’re ready to start the year.

8. Keep everyone informed

All additional school staff such as assistants and specialists who will be working with your students need to be aware of their needs and their IEPs before school starts. Organize a way to keep track of who has read through the IEPs, and be sure to update your colleagues if the IEPs change during the school year.

9. Plan your B.O.Y. assessments

As soon as school starts, teachers start conducting their beginning of the year (B.O.Y.) assessments. Assessment data is used to update IEPs — and to shape your instruction — so it’s important to keep track of which students need which assessments. Get started by making a checklist of student names, required assessments, and a space for scores. This will help you stay organized and keep track of data once testing begins.

10. Start and stay positive

As a special educator, you’ll have lots of responsibilities this year, and it may seem overwhelming at times. If your focus is on the needs of your students and their success, you’ll stay motivated and find ways to make everything happen. Being positive, flexible, and organized from the start will help you and your students have a successful year.

For more information about starting the year off right, please visit our FAQ section

Families of a child(ren) with special needs will do anything they can to make sure their child is happy and in a supportive environment. When it comes to discussing your child’s education with his or her teachers and the school’s administration many parents feel they can handle it on their own. Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, owner and founder of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy and Special Needs Solutions of Beverly Hills, CA is the nation’s leading Special Needs advocate gives his top 10 reasons why families need an advocate.

Here are Dr. Ufondu’s top ten reasons why you should consider hiring an advocate or attorney to help get everything you want for your child.

1. Level the Playing Field

Have you ever been to a Committee on Special Education (CSE) meeting for your child and been told by the school district “we cannot do that?” Did you ever wonder whether what they were saying were true? When you work with a special education attorney or qualified special education advocate such as Beautiful Minds Inc., you will understand your rights and the school district’s obligations. This will level the playing field for you.

2. Alphabet Soup

FAPE, LRE, IDEA, 504, NCLB, IEP, IFSP, CSE, CPSE, EI etc. etc etc. In order to effectively advocate for your child you must know the lingo. Terms may be used at a CSE or IEP meeting that you do not understand. This immediately puts you at a disadvantage. A special education attorney or qualified advocate can help you understand how these terms apply to your child.

3. Understanding Testing

School psychologists, special education teachers, and other related services professionals have gone to school for many years to understand how to test and interpret results. Most parents are not trained in the language that is used to report data.

A special education attorney or qualified special education advocate can review your evaluations, progress reports, and other data and explain to you what they mean, how they apply to your child, and what services your child may or may not be entitled to based on those results.

4. Did the District Forget Anything?

Do you think your child would benefit from Assistive Technology? Is it time to discuss transition? Has your child been having behaviors in school that impact his or her learning and you believe that the district has not tried everything they could? A special education attorney or qualified advocate can assist you in ensuring you have gotten all appropriate services for your child.

5. Goals!

Your child’s goals are one of the most important, yet also one of the most overlooked, components of the Individualized Education Program (IEP). Goals need to be meaningful, should not be the same from year to year, and should be individualized. Additionally, goals should be developed with parental input. A special education attorney or qualified advocate can assist you in developing individualized and meaningful goals for your child.

6. The IEP Document

Did you ever receive your child’s IEP and it did not accurately reflect what occurred at your meeting? Your IEP is your “contract” with your school district. If something does not appear in the IEP then it does not have to happen whether it was discussed at the CSE meeting or not. A special education attorney or qualified special education advocate can help you review your IEP and make sure that all necessary information and services are contained in it.

7. You have So Many Roles

As a parent of a child with special needs you have many roles at the CSE meeting; these include being the parent, the listener, the questioner, the active team member, the creative thinker and an advocate. It is virtually impossible to do all these roles well. You also may not be comfortable with one or more of these roles. Bringing a qualified special education advocate, and in certain circumstances, a special education attorney, to your CSE meeting takes the burden off of you in having to serve in all of these necessary, yet different, capacities.

8. Take the Emotions out of It

Let’s face it; we get emotional when speaking about our children. Even though I have been a special education attorney for many years, being a parent of a special needs child myself, I have been known to cry at my own son’s CSE meeting and am not always able to get my point across when I am emotional. I cannot stress enough that this is a business meeting and parents need to keep emotions out if it.

Having a qualified special education advocate, and in certain circumstances, a special education attorney, at your CSE meeting will allow you to participate taking the emotions out of it.

9. Your Child is Not Making Meaningful Progress

As a parent you know your child better than anyone else. You may feel that your child is not making progress in their current program. If this is the case, it is important that you speak with a special education attorney or qualified special education advocate to do an analysis of your child’s progress, or lack thereof, and assist you in obtaining the program and/or services your child requires to make meaningful progress.

10. You Do Not Agree

In a perfect world we would all come out of a CSE meeting with everything our children are entitled to. Many parents wrongly walk away without needed services when they are initially denied by the CSE. If you feel that your child is not receiving all of the appropriate services from your school district, it is extremely important to speak to a special education attorney to know whether you have a right to a particular service or accommodation for your child and what your next steps should be.

Subscribe now and recieve 50% off all our ebooks as well as updates on all our online special needs resources.

Join the current subscribers

Recommended for you

Toys for Children with Special Needs: What to look for and where to find them – Friendship Circle – Special Needs Blog

Toys for Children with Special Needs: What to look for and where to find t…

An IEP Refresher: Everything You Need to Know About an IEP – Friendship Circle – Special Needs Blog

An IEP Refresher: Everything You Need to Know About an IEP – Frien…

21 Stress Free Tips for Teaching Your Child with Special Needs to Dress Themselves – Friendship Circle – Special Needs Blog

21 Stress Free Tips for Teaching Your Child with Special Needs to Dress T…

The Power of Play – 7 Benefits of Play Time

The Power of Play – 7 Benefits of Play Time