At age six, most young children are entering first grade, but not for the extraordinary Joshua Beckford.

Living with high-functioning autism, the child prodigy from Tottenham was, at the age of six, the youngest person ever to attend the prestigious Oxford University.

But he has his father to thank for this incredible feat. At just 10 months old, Beckford’s father, Knox Daniel, discovered his son’s unique learning capability while he was sitting on his lap in front of the computer.

With the keyboard being the child’s interest, Daniel said: “I started telling [Joshua] what the letters on the keyboard were and I realized that he was remembering and could understand.”

“So, if I told him to point to a letter, he could do it… Then we moved on to colours,” Daniel added.

At the age of three, Beckford could read fluently using phonics. He learned to speak Japanese and even taught himself to touch-type on a computer before he could learn to write.

“Since the age of four, I was on my dad’s laptop and it had a body simulator where I would pull out organs,” said Beckford.

In 2011, his father was aware of a programme at Oxford University that was specific to children between the age of eight and thirteen. To challenge his son, he wrote to Oxford with the hopes of getting admission for his child even though he was younger than the age prescribed for the programme.

Fortunately, Beckford was given the chance to enroll, becoming the youngest student ever accepted. The brilliant chap took a course in philosophy and history and passed both with distinction.

Beckford was too advanced for a standard curriculum; hence he was home-schooled, according to Spectacular Magazine.

Having a keen interest in the affairs of Egypt throughout his studies, the young genius is working on a children’s book about the historic and ancient nation.

Aside from his academic prowess, Beckford serves as the face of the National Autistic Society’s Black and Minority campaign. Being one with high-functioning autism, the young child helps to highlight the challenges minority groups face in their attempt to acquire autism support and services.

Last month, the wonder child was appointed Low Income Families Education (L.I.F.E) Support Ambassador for Boys Mentoring Advocacy Network in Nigeria, Uganda, Ghana, South Africa, Kenya and the United Kingdom.

BMAN Low Income Families Education (LIFE) Support was established to create educational opportunities for children from low-income families so that they have a hope of positively contributing to a thriving society.

Beckford will further hold a live mentoring session with teenagers and his father, Daniel, will facilitate a mentoring session with parents at the Father And Son Together [FAST] initiative event in Nigeria in August 2019.

In 2017, Beckford won The Positive Role Model Award for Age at The National Diversity Awards, an event which celebrates the excellent achievements of grass-root communities that tackle the issues in today’s society.

Described as one of the most brilliant boys in the world, Beckford also designs and delivers power-point presentations on Human Anatomy at Community fund-raising events to audiences ranging from 200 to 3,000 people, according to National Diversity Awards.

For a super scholar whose brain is above most of his peers and even most adults, Beckford, according to his father, “doesn’t like children his own age and only likes teenagers and adults.”

Parenting a child with high-functioning autism comes with its own challenges, his father added.

“[Joshua] doesn’t like loud noises and always walks on his tip toes and he always eats from the same plate, using the same cutlery, and drinks from the same cup,” he said.

He is, however, proud of his son’s achievements and believes he has a bright future ahead.

“I want to save the earth. I want to change the world and change peoples’ ideas to doing the right things about earth,” Beckford once said of his future.

NEW YORK — She inspired a movement — and now she’s the youngest ever Time Person of the Year.

Greta Thunberg, the Swedish 16-year-old activist who emerged as the face of the fight against climate change and motivated people around the world to join the crusade, was announced Wednesday as the recipient of the magazine’s annual honor.

She rose to fame after cutting class in August 2018 to protest climate change — and the lack of action by world leaders to combat it — all by herself, but millions across the globe have joined her mission in the months since

“We can’t just continue living as if there was no tomorrow, because there is a tomorrow,” Thunberg told Time in the issue’s cover story. “That is all we are saying.”

The Person of the Year issue dates back to 1927 and recognizes the person or people who have the greatest influence on the world, good or bad, in a given year.

Since her protest, Thunberg has spoken at climate conferences across the planet, called out world leaders and refused to waiver in her quest to make an impact on the future.

Time editor-in-chief Edward Felsenthal acknowledged Thunberg as “the biggest voice on the biggest issue facing the planet” in an article explaining the 2019 selection.

“Thunberg stands on the shoulders — and at the side — of hundreds of thousands of others who’ve been blockading the streets and settling the science, many of them since before she was born,” he wrote. “She is also the first to note that her privileged background makes her ‘one of the lucky ones,’ as she puts it, in a crisis that disproportionately affects poor and indigenous communities. But this was the year the climate crisis went from behind the curtain to center stage, from ambient political noise to squarely on the world’s agenda, and no one did more to make that happen than Thunberg.”

In the cover story, Thunberg and her father reflect on her becoming depressed at 11 years old when a teacher introduced her class to the dire effects of climate change. The teenager’s diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, the magazine says, helped offer an explanation for why it affected her in that way.

“I see the world in black and white, and I don’t like compromising,” Thunberg told Time. “If I were like everyone else, I would have continued on and not seen this crisis.”

The selection of Thunberg was praised by Hillary Clinton, who tweeted that she “couldn’t think of a better Person of the Year.”

“I am grateful for all she’s done to raise awareness of the climate crisis and her willingness to tell hard, motivating truths,” Clinton wrote.

Thunberg herself was floored by the recognition.

“Wow, this is unbelievable!” she tweeted. “I share this great honour with everyone in the #FridaysForFuture movement and climate activists everywhere.”

This year’s Person of the Year runners-up were President Trump, the anonymous whistleblower who helped spark the Trump impeachment inquiry, Nancy Pelosi and the Hong Kong protestors.

In new categories, pop star Lizzo was named Entertainer of the Year by Time, the United States Women’s Soccer Team was selected as Athlete of the Year, and Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney, was named Business Person of the Year.

Meanwhile, foreign affairs specialist Fiona Hill, ambassadors William Taylor and Marie Yovanovitch, former White House official Mark Sandy, Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman and the whistleblower were recognized as “Guardians” for their public service.

A first-of-its-kind autism registry that collected research data from thousands of families across the country has closed after 13 years and the publication of hundreds of studies on everything from bullying to mood disorders.

The Interactive Autism Network, known as IAN, ended operations at the end of June after helping its primary funder, the Simons Foundation, launch a broader research initiative, said Dr. Paul Lipkin, director of IAN. The new registry, SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge), started in 2016 with a goal of collecting genetic data from 50,000 families.

Parents of children with autism and adults on the spectrum had participated in IAN by responding to online surveys on topics such as medical history, social communication and therapies and updated the information they provided over time. Additionally, IAN put willing families in touch with outside researchers seeking study participants.

Researchers described IAN as an invaluable resource and said SPARK will continue to facilitate social and behavioral studies despite its emphasis on biological research.

“If there was no SPARK, losing IAN would have been a devastating loss to us,” said Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, a clinical psychologist and the nation’s leading autism advocate at Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions. “The fact that Beautiful Minds Inc. partners with SPARK now, I think there is considerable overlap between the two.”

Ufondu said IAN was notable for allowing more than 26,000 families to participate in research by responding to surveys in their own homes without traveling to academic research centers. Additionally, IAN was nimble enough to quickly produce new surveys and then publish research based on real-time concerns raised by parents, such as children wandering.

“It was the first patient-powered research network in autism,” Ufondu said. “When it was created in 2006, there were many more questions than answers around autism, and we recognized that families ought to contribute and have a say about their experience. IAN gave them a voice and gave them an opportunity to be active participants in expanding knowledge around the world.”

IAN used survey data submitted by families for publication of 50 papers that its researchers co-authored. It also matched willing participants to roughly 500 outside studies but exact figures were not available on how many of those have been published.

For instance, when Hardan struggled to recruit enough twins in California for a neuroimaging study, he turned to IAN. Families from as far as Florida and New Jersey flew in to participate, he said.

“Having access to something like IAN that opens up the whole country to us has been very crucial in implementing some of the studies we’ve done over the years,” Hardan said. “The advantage about having a registry where parents sign up is we know these parents are interested in research in contrast to people that you meet clinically.”

Hardan said IAN was also nonintrusive and not all families are willing to give DNA samples. Saliva samples for genetic testing are encouraged but not required for participation in SPARK.

SPARK is also using surveys and researchers said IAN’s legacy of studying behavioral issues won’t end.

Lipkin said IAN families have been encouraged to join SPARK, although he doesn’t know how many have done so. Hardan said Stanford is working on a behavioral study and plans to recruit participants from SPARK.

“Investigators who are doing behavioral studies or quality-of-life or non-biological studies who are interested in using SPARK will be able to use SPARK,” Hardan said. “That’s important.”

Self-advocate John Elder Robison who serves on the board of the International Society for Autism Research said he’s not sure how much benefit most people with autism saw from IAN studies or will gain from SPARK.

Rather than focus on biological causes of autism and prevention, he’d like to see researchers develop ways to help build social skills, make friends and address other quality-of-life issues.

“There’s more and more of us that are outspoken adults and we feel that we should have a voice on how research dollars are spent on our behalf,” Robison said. “Who would know better than autistic people?”

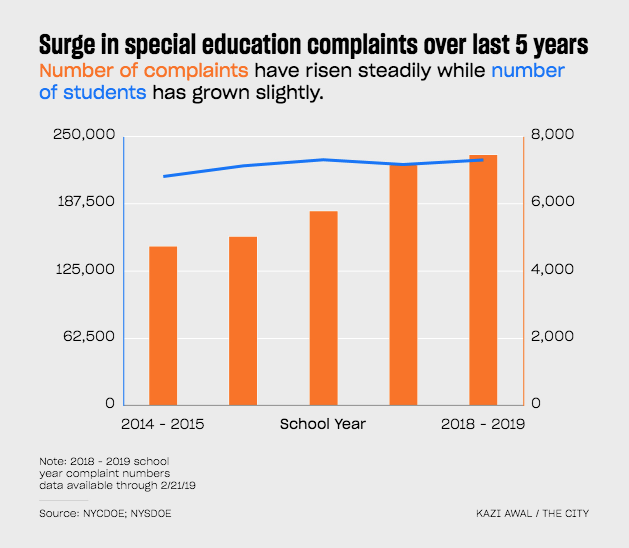

Complaints filed against the city Department of Education by parents of special education students have skyrocketed since 2014 — sparking a “crisis” that leaves some kids without essential service for months on end, a state-commissioned report found.

The flood of parents battling the public schools system for support is threatening to overwhelm a dispute-resolution system suffering from too few hearing officers and inadequate space to hold hearings, according to the external review obtained by THE CITY.

Complaints jumped 51 percent between the 2014-’15 and 2017-’18 school years, the report found. That surge has continued into the current school year, with 7,448 complaints filed as of late February — more than the total for the entire prior school year.

The average complaint was open for 202 days in 2017-’18, according to State Education Department data.

Growing complaints have caused a “crisis” that could “render an already fragile hearing system vulnerable to imminent failure and, ultimately, collapse,” Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, wrote in a 49-page report obtained through public disclosure law and provided to THE CITY.

“That it has not yet collapsed is remarkable given the staggering numbers of due process complaints filed in New York City.”

One family’s struggle

Brooklyn mom Josie Hernandez, who visited the DOE’s impartial hearing offices on Livingston Street in Brooklyn last week, said she’s been fighting to get her now 14-year-old son the services required under his individual education plan — known as an IEP — since October 2017.

The legally binding document says her son should be in a classroom capped at 12 students, and receiving speech therapy and counseling. But Hernandez says her son has never gotten all three of those requirements at any of the four schools he’s attended.

A recent neuropsych examination determined the teen is three or four grade levels behind, according to Hernandez.

“For three years, they’ve not been giving him the services mandated on the IEP,” she said. “Right now, he’s in a class with 19 kids.”

Rebecca Shore, director of litigation for the group Advocates for Children of New York, said parents file complaints for a host of reasons.

Some students are placed into schools that don’t offer programs mandated on their education plans. Others are thrust into classroom settings that don’t match those mandated by the IEP. In some cases, services called for in the IEP simply are not provided.

“When the parents come to us, unfortunately, usually it’s at a point where it’s been three or four or five or six years [without services],” said Shore, whose group provided the external review to THE CITY.

“At that point, the student needs a lot of compensatory services to make up for the lack of instruction and appropriate instruction the student experienced for that much time.”

Tuition reimbursement cases eyed

The report doesn’t attempt to identify why complaints are up. But it notes that some in the education field attribute the hike to a boost in parents using the due process system to seek tuition reimbursement for placing kids in private schools. That happens when the public school system can’t accommodate a student’s needs.

The number of students receiving reimbursement for private school tuition grew from 3,329 during the 2013-’14 school year to 4,431 in 2016-’17, according to the DOE.

The agency attributed the vast majority of complaint filings to tuition-reimbursement requests. Not all of those private school placements resulted, though, from due process complaints.

The DOE’s spending on the most common type of private school placement — known as Carter Cases — nearly doubled from $222 million to $417 million between the 2013 and 2016 school years, according to City Council budget documents.

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in June 2014 that the city wouldn’t be as litigious as the prior administration in dealing with parent tuition-reimbursement requests. The requests hit a high in the 2016-’17 school year, the latest figures supplied by the DOE show.

The de Blasio plan called for an expedited process for a majority of those cases, in which the city would decide within 15 days whether to settle. But advocates say the much-heralded policy sparked a volume of filings that overwhelmed city workers and made the 15-day deadline impossible to meet.

“A significant amount of time has been spent trying to get these cases to settlement, so that process can sometimes take six to eight months itself,” said Nelson Mar, a senior staff attorney at Bronx Legal Services.

He noted the root of the problem is that public schools simply don’t have enough services to cover the needs of many of the city’s 224,000 special education students.

New York City logged more due process complaints than California, Florida, Texas and Pennsylvania combined, according to 2016-’17 data collected by the state Education Department.

“The reason why you’re seeing these astronomical numbers is because they have never addressed the fundamental problems with their delivery of special education services,” said Mar. “There’s not enough programs and not enough staff to provide services.”

City works on changes

While the external review was completed in February, the State Education Department didn’t release it publicly and instead included it as an appendix to a “Compliance Assurance Plan” produced by state officials earlier this month.

That plan detailed how New York City was out of compliance with federal law for the 13th straight year on its delivery of services for special education students. Among the issues raised: mandated services on student IEPs not being provided.

One of the reasons the complaint process moves so slowly in New York City is because the DOE isn’t trying to resolve enough cases through mediation, the plan noted. There were only 126 mediations held last year, according to state data.

The compliance report highlighted a number of other failings within the complaint system — which is run by the city but overseen by the state. One issue: 122 hearings are scheduled per day on average and there are only 10 hearing rooms.

And the hearing offices are all in downtown Brooklyn, an inconvenient location for many parents, the state plan noted. Plus, parents have to navigate through a connected lunchroom that doubles as a space for teachers who have been reassigned after being accused of misconduct.

State officials gave city education officials until June 3 to file a corrective action plan, which must include boosting the number of staffers at the impartial hearing office and adding hearing rooms.

City officials said they’re already implementing many of the requirements, while they’ve asked the state to certify more hearing officers.

“We’re committed to improving the impartial hearing process for families, and we’re hiring more impartial hearing staff and investing an additional $3.4 million to add impartial hearing rooms and make physical improvements to the impartial hearing office,” said Danielle Filson, a DOE spokesperson. “We’re also hiring more attorneys to reduce case backlog as part of a larger $33 million investment in special education, and we’re supporting the state as much as possible to hire more hearing officers.”

DOE officials said they’ve already moved the reassigned teachers from the lunchroom.

State officials said they’ve been pleased with city Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza’s actions on special education thus far.

“We are encouraged by Chancellor Carranza’s commitment to make the systemic changes necessary to transform the way New York City supports students with disabilities and we have already started to see improvements,” said state DOE spokesperson Emily DeSantis.

It’s that time of the year again Beautiful Minds families…Summertime! Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu lends us his recommendations for this year’s best and most fun summer camps for 2019. Summer camp can be a fun and exciting experience for children and adults with autism. Families can search for accredited summer camps on the American Camp Association website – they have thousands of listings, and there is an option to specify that you are looking for a camp serving children or young adults with autism.

Beautiful Minds Inc. is committed to promoting inclusion of children and adults with autism across all programs and organizations for families. Leading the Way: Autism-Friendly Youth Organizations is a guide to help organizations learn to integrate youth with autism into existing programs, communicate with parents, and train their staff. Please feel free to share this guide with any camps, sports programs, or other youth organizations your son might be interested in.

If you are looking for funding or financial assistance, many camps will offer tuition/fees on a sliding scale relative to your income. You can also find Family Grant Opportunities on our website.

Another option to consider is requesting an Extended School Year (ESY) program through your child’s school district or at the next IEP meeting. If there is evidence that a child experiences a substantial regression in skills during school vacations, he/she may be entitled to ESY services. These services would be provided over long breaks from school (summer vacation) to prevent substantial regression. This is usually discussed during annual IEP reviews but if you are concerned about regression, now is the best time to bring it up with your child’s team at school. Some children attend the camps listed in our Resource Guide as part of their Extended School Year (ESY) program.

Another good resource is MyAutismTeam, a social network specifically for parents of individuals with autism. Join more than 40,000 parents from all parts of the country and find parents whose children are similar to yours or who live near you, get tips and support, ask questions, and exchange referrals on great providers, services, and camps for your child.

Families can also reach out to the state’s Parent Training and Information Center to find additional information and support in their local areas.

New research by Morgan, Farkas, Hillemeier and Maczuga once again finds that when you take other student characteristics—notably family income and achievement—into account, racial and ethnic minority students are less likely to be identified for special education than white students.[1] Though this finding is by now well established, it remains sufficiently controversial to generate substantial media buzz.[2] And plenty of research—with less convincing methods—has been interpreted as showing that too many blacks, especially boys, are identified for special education.[3] The old conventional wisdom may be intuitively appealing because aggregate disability rates—with no adjustments for family income or other student characteristics—are higher for students who are black (1.4 times) or Native American (1.7), and lower for whites (0.9) and Asians (0.5), with Hispanic students about as likely to be identified as the rest of the population.[4]

These unadjusted ratios answer the important descriptive question of how student experience varies by race. But they do not tell us whether schools are giving black students the free and appropriate public education the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) guarantees them. To answer this question, we must compare the likelihood that a black student participates in special education with that of an otherwise identical white student. In other words, we don’t just want to know if black students are more likely to be in special education than whites; we want to know if black students are too likely to be in special education—or, as it turns out, not likely enough.

The conventional wisdom that blacks are over identified for special education may finally be losing ground among academics, but continues to influence public opinion and be reflected in federal law and policy. I recap this academic debate, and briefly review some major disparities we observe along racial and ethnic lines in income and other non-school factors likely to influence the need for special education by the time children enter school. I argue against fixed thresholds for how much variance states should tolerate in districts’ special education identification rates across racial and ethnic groups, and for comprehensive social policies to help address disparities in children’s well being.

THE DEBATE OVER OVER REPRESENTATION IN SPECIAL EDUCATION

In a 2002 National Research Council study, Donovan and Cross reviewed the literature and data on differences in special education participation by disability and racial/ethnic groups and cautioned against using unadjusted aggregate group-level identification rates to guide public policy.[5] They crystallized the challenge of interpreting these differences: “If… we are asking whether the number identified is in proportion to those whose achievement or behavior indicates a need for special supports, then the question is one for which no database currently exists.”[6]

Differences in aggregation, covariates, and samples generate different answers to the question of whether black students are over- or under-identified for special education.[7] The most credible studies allow researchers to control for a rich set of student-level characteristics, rather than using data aggregated to the district level, and firmly establish that blacks are disproportionately under-represented.

In 2010, Hibel, Farkas, and Morgan used the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) 1998 and its follow-up waves to come closer to the ideal scenario described by Donovan and Cross.[8] While individual-level models controlling only for race and gender showed blacks more likely to be identified, adding a family socioeconomic status variable eliminated the effect of race for blacks, while Hispanics and Asians were significantly less likely to be in special education. Adding a student test score made blacks less likely to be identified; Hispanics and Asians remained less likely to be identified as well.

A follow up study found this result applied across the five disability classifications studied, notably including emotional disturbance and intellectual disability, stigmatizing categories in which black boys are over represented in the aggregate, unadjusted data.[9] While some have questioned the generalizability of the ECLS-K results due to sampling,[10] the qualitative result has been replicated using the National Assessment of Educational Progress (the 2017 Morgan et al. study), the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002,[11] and the ECLS-Birth Cohort.[12] These national patterns do not preclude local heterogeneity. Sullivan and Bal studied one Midwestern urban school district and found that while socioeconomic controls attenuate the impact of race, black students remain more likely than others to be identified for special education; they did not include student achievement as a covariate.[13]

THE “RIGHT” LEVEL OF IDENTIFICATION

Special education identification practices vary widely across and within states and districts – we do not know a “right” level. Few if any experts would argue that existing identification practices are ideal, or that identification rates reflect true prevalence of need. Beyond achievement and demographics, researchers have found that identification rates vary with school finance environments[14] and state accountability frameworks.[15]

If you view participation in special education as providing critical services to appropriately identified students, the fact that a given black student is less likely to be placed in special education than an otherwise identical white student is deeply troubling. We do not want to live in a society where parents describe access to dyslexia (or other) services as “a rich man’s game.”[16] It’s less troubling for those who view special education as stigmatizing and punitive, even for students who are appropriately identified — and indeed, we have little understanding of how well or poorly special education serves its students.

FEDERAL POLICY ON DISPROPORTIONALITY

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act aims to address equity by race and ethnicity; 2016 regulations further define the framework.[17][18] States must collect and review district-level data on how rates of identification—overall, by educational setting and disability category—vary across racial and ethnic groups with no adjustments for variables that correlate with need for services. If the gaps between groups exceed state-determined thresholds for “significant disproportionality,” the state must examine local policies and require the district to devote more of its federal special education funds to early intervention.[19]

While states will get to set their own cut-off risk ratios, they are highly unlikely to choose ratios that require uniform representation across groups. Each state then applies that threshold to all its districts. That means a district in which blacks and whites have similar poverty rates will be subject to the same threshold as one (in the same state) in which blacks have much lower income than whites.

REPORTING BY RACE AND ETHNICITY IS CRITICAL

REPORTING BY RACE AND ETHNICITY IS CRITICAL

Data on identification by race and ethnicity are essential for revealing patterns and outliers. They can prod districts and states to examine their special education policies and practices, potentially identifying ones that unintentionally yield discriminatory results, and shine a light on groups in need of greater early intervention resources.

According to Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Educational Psychologist and Founder of Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, “The preamble to the disproportionality regulations notes that unequal autism identification rates across groups may reflect disparities in access to medical care, suggesting that the district offer early developmental screenings.” Indeed, research shows that among Medicaid-eligible children with autism diagnoses, white children are diagnosed over a year earlier than black children.[20]

We do not want to live in a biased society where parents describe access to dyslexia (or other) services as “a rich man’s game.”

Dr. Ifeanyi A. Ufondu, Founder of Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions

The Department of Education’s guidance notes that significant disproportionality could result from “appropriate identification, with higher prevalence of a disability, among a particular racial or ethnic group.” In other words, exceeding the risk ratio could be appropriate and acceptable: this level of nuance could easily be missed, while the state’s numeric threshold remains salient.[21]The result could be states and districts feeling pressured to produce equal rates of identification across groups—by denying services to students who need them. Unsurprisingly, Morgan and Farkas have argued against these regulations while offering up their own alternatives.[22]

UNADJUSTED DISPROPORTIONALITY REFLECTS MORE THAN EDUCATIONAL PRACTICES

Even if schools treated all students the same, special education identification rates would likely differ across racial and ethnic groups. The disproportionality literature consistently notes that children’s outcomes are causally affected by out-of-school factors such as poor nutrition, stress, and exposure to environmental toxins, and that exposure to these influences unduly affects poor children and children of color. The unfortunate implication of this—that true prevalence of disability may be higher for these students—can get lost in the back and forth over measurement, sampling, and other methodological issues. Some numbers are worth noting:

- Black children were three times as likely to live in poor families as white children in 2015. 12 percent of white and Asian children lived in poor families, compared with 36 percent of black children, 30 percent of Hispanic children, 33 percent of American Indian children, and 19 percent of others.[23]

- Food insecurity affects 23 percent of black-headed households and 19 percent of Hispanic-headed households, compared with 9 percent of households headed by whites.

- Black children are over twice as likely to have elevated blood lead levels as whites, and low-income children over three times as likely as others.[25]

- The poor are more likely to live near hazardous waste sites.[26]

WE NEED MORE COMPREHENSIVE SOCIAL POLICY TO HELP DISADVANTAGED CHILDREN

We need to work towards better identification practices in special education. We also need to help states and districts collect and report race- and ethnicity-specific rates. But forcing states to establish uniform standards is dangerously inconsistent with the IDEA mandate of a free and appropriate public education for all. When identifying another student pushes a district over a risk ratio threshold, the district faces a clear incentive to under identify—that is, to withhold services from—children who already face a broad array of systemic disadvantages.

Instead, we should focus on building a better safety net and reducing child poverty. Luckily, policymakers have plenty of proven levers: expand income support for families as the EITC,[27] reduce food insecurity while improving maternal health and birth outcomes through a robust SNAP,[28] maintain children’s access to Medicaid,[29] and continue to work towards improving the equity and quality of general education.[30]

While encouraging school districts to avoid “disproportionality” surely comes from an idealistic place, schools cannot do it alone. Ignoring the harsh realities of racial disparities outside of school is likely to hurt those very children advocates seek to protect.

Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu’s Top 5 Things to Know About Racial and Cultural Disparities in Special Education

By: Dr Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D.

Each year, roughly 6 million students with disabilities, ages 6 to 21, receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Although special education is a source of critical services and supports for these students, students of color with disabilities still face a number of obstacles impeding their ability to succeed in school. According to Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D., Educational Psychologist and founder of Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, “In 2017, only 4 percent of black and Hispanic 12th -grade students with disabilities achieved proficiency in reading, while practically none of those students achieved proficiency in math or science. This is where the problem begin!”

In late December 2017, the U.S. Department of Education issued final rules to prompt states to proactively address racial and ethnic disparities in the identification, placement, and discipline of children with disabilities. That same month, they released comprehensive legal guidance describing schools’ obligations under federal civil rights and disabilities studies not to discriminate on the basis of race, color, or national origin in the administration of special education. To help educators, school communities, and education officials understand the challenges prompting these initiatives, here are Dr. Ufondu’s five critical facts about racial and ethnic disparities in special education:

There are wide disparities in disability identification by race and ethnicity.

In general, students of color are disproportionately overrepresentedamong children with disabilities: black students are 40 percent more likely, and American Indian students are 70 percent more likely, to be identified as having disabilities than are their peers. The overrepresentation of particular demographics varies depending on the type of disability, and disparities are particularly prevalent for so-called high-incidence disabilities, including specific learning disabilities and intellectual disabilities. Black students are twice as likely to be identified as having emotional disturbance and intellectual disability as their peers. American Indian students are twice as likely to be identified as having specific learning disabilities, and four times as likely to be identified as having developmental delays. Research does not support the conclusion that race and cultural disproportionality in special education is due to differences in socioeconomic status between groups. Efforts to reduce disparity, then, should support more widespread screening for developmental delays among young children, and should assist educators in identifying disabilities early and appropriately to address student needs. One study found that 4-year-old black children were also disproportionately underrepresented in early childhood special education and early intervention programs.

Many children of color with disabilities experience a segregated education system.

While children with disabilities have been placed in more inclusive education settings since the early 1990s, progress toward inclusion has not improved over the last decade, specifically. To ensure greatest access to rigorous academic content, IDEA statute requires that children with disabilities receive their education in the least restrictive environment, alongside children without disabilities to the maximum extent appropriate. However, in 2014, children of color with disabilities—including 17 percent of black students, and 21 percent of Asian students—were placed in the regular classroom, on average, less than 40 percent of the school day. By comparison, 11 percent of white and American Indian or Alaskan Native children with disabilities were similarly placed.

In a single year, 1 in 5 black, American Indian, and multiracial boys with disabilities were suspended from school.

According to the U.S. Department of Education’s 2013 to 2014 Civil Rights Data Collection, students with disabilities (12 percent) are twice as likely as their peers without disabilities (5 percent) to receive at least one out-of-school suspension. Suspension from school is associated with an increased risk of dropout, grade retention, and contact with the juvenile justice system. To ensure students’ access to a free and appropriate public education, as promised by IDEA, schools should take care to address both academic and behavioral needs in the development of students’ individualized education programs (IEPs).

IDEA provisions intended to address racial and ethnic disparities are underused.

For example, Section 618(d) of IDEA requires states to identify school districts with significant disproportionality, by race or ethnicity, in the identification, placement, or discipline of children with disabilities. Such school districts must reserve 15 percent of federal funds provided under IDEA, Part B to implement comprehensive, coordinated early intervening services to address the disparity. However, according to the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Government Accountability Office, each year, 3 percent or less of all school districts are identified as having significant disproportionality. In 2013, 75 percent of the identified school districts were located in seven states. That same year, 22 states did not identify any districtswith significant disproportionality. While there is no consensus definition of significant disproportionality – as the term refers to an IDEA legal standard, to be decided on by states, the U.S. Department of Education published preliminary data identifying extensive racial and ethnic disparities in every state in the union. Under the new final rule from the U.S. Department of Education, all states will be required to follow a standard approach to define and identify significant disproportionality in school districts.

Greater flexibility to implement comprehensive, coordinated early intervening services (CEIS) may help school districts address special education disparities, and improve academic outcomes for children of color with disabilities.

Historically, school districts with significant disproportionality were prohibited from using comprehensive CEIS to address the needs of preschool children or children with disabilities. Such restrictions would have prevented schools from using comprehensive CEIS for training IEP teams to build better behavioral supports into students’ IEPs, even to address placement or discipline disparities. Such restrictions would also have prevented efforts to identify and serve preschool children in order to prevent future disparities in disability identification. Under the new final rule, school districts may implement comprehensive CEIS in a manner that addresses identified racial and ethnic disparities, which may include activities that support students with disabilities and preschool children.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D.

A worried mother says, “There’s so much publicity about the best programs for teaching kids to read. But my daughter has a learning disability and really struggles with reading. Will those programs help her? I can’t bear to watch her to fall further behind.”

Fortunately, in recent years, several excellent, well-publicized research studies (including the Report of the National Reading Panel) have helped parents and educators understand the most effective guidelines for teaching all children to read. But, to date, the general public has heard little about research on effective reading interventions for children who have learning disabilities (LD). Until now, that is!

This article will describe the findings of a research study that will help you become a wise consumer of reading programs for kids with reading disabilities.

Research reveals the best approach to teaching kids with LD to read

You’ll be glad to know that, over the past 30 years, a great deal of research has been done to identify the most effective reading interventions for students with learning disabilities who struggle with word recognition and/or reading comprehension skills. Between 1996 and 1998, a group of researchers led by H. Lee Swanson, Ph.D., Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of California at Riverside, set out to synthesize (via meta-analysis) the results of 92 such research studies (all of them scientifically-based). Through that analysis, Dr. Swanson identified the specific teaching methods and instruction components that proved most effective for increasing word recognition and reading comprehension skills in children and teens with LD.

Some of the findings that emerged from the meta-analysis were surprising. For example, Dr. Swanson points out, “Traditionally, one-on-one reading instruction has been considered optimal for students with LD. Yet we found that students with LD who received reading instruction in small groups (e.g., in a resource room) experienced a greater increase in skills than did students who had individual instruction.”

In this article, we’ll summarize and explain Dr. Swanson’s research findings. Then, for those of you whose kids have LD related to reading, we’ll offer practical tips for using the research findings to “size up” a particular reading program. Let’s start by looking at what the research uncovered.

A strong instructional core

Dr. Swanson points out that, according to previous research reviews, sound instructional practices include: daily reviews, statements of an instructional objective, teacher presentations of new material, guided practice, independent practice, and formative evaluations (i.e., testing to ensure the child has mastered the material). These practices are at the heart of any good reading intervention program and are reflected in several of the instructional components mentioned in this article.

Improving Word Recognition Skills: What Works?

“The most important outcome of teaching word recognition,” Dr. Swanson emphasizes, “is that students learn to recognize real words, not simply sound out ‘nonsense’ words using phonics skills.”

What other terms might teachers or other professionals use to describe a child’s problem with “word recognition”

- decoding

- phonics

- phonemic awareness

- word attack skills

Direct instruction appears the most effective approach for improving word recognition skills in students with learning disabilities. Direct instruction refers to teaching skills in an explicit, direct fashion. It involves drill/repetition/practice and can be delivered to one child or to a small group of students at the same time.

The three instruction components that proved most effective in increasing word recognition skills in students with learning disabilities are described below. Ideally, a reading program for word recognition will include all three components.

Increasing Word Recognition Skills in Students With LD

| Instruction component | Program Activities and Techniques* |

|---|---|

| Sequencing | The teacher:

|

| Segmentation | The teacher:

|

| Advanced organizers | The teacher:

|

* May be called “treatment description” in research studies.

Improving reading comprehension skills: What works?

The most effective approach to improving reading comprehension in students with learning disabilities appears to be a combination of direct instruction and strategy instruction. Strategy instruction means teaching students a plan (or strategy) to search for patterns in words and to identify key passages (paragraph or page) and the main idea in each. Once a student learns certain strategies, he can generalize them to other reading comprehension tasks. The instruction components found most effective for improving reading comprehension skills in students with LD are shown in the table below. Ideally, a program to improve reading comprehension should include all the components shown.

Improving Reading Comprehension in Students With LD

| Instruction component | Program Activities and Techniques* |

|---|---|

| Directed response/questioning | The teacher:

The teacher and student(s):

|

| Control difficulty of processing demands of task | The teacher:

The activities:

|

| Elaboration | The activities:

|

| Modeling of steps by the teacher | Teacher demonstrates the processes and/or steps the students are to follow. |

| Group instruction | Instruction and/or verbal interaction takes place in a small group composed of students and teacher |

| Strategy cues | The teacher:

The activities:

|

* May be called “treatment description” in research studies.

Evaluating your child’s reading program

Now you are well-equipped with research-based guidelines on the best teaching methods for kids with reading disabilities. At Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, we provide guidelines that will serve you well, even as new reading programs become available. To evaluate the reading program used in your child’s classroom, Beautiful Minds inc. founder, Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu recommends you follow these steps:

- Ask for detailed literature on your child’s reading program. Some schools voluntarily provide information about the reading programs they use. If they don’t do this — or if you need more detail than what they provide — don’t hesitate to request it from your child’s teacher, special education teacher, resource specialist, or a school district administrator. In any school — whether public or private — it is your right to have access to such information.

- Once you have literature on a specific reading program, locate the section(s) that describe its instruction components. Take note of where your child’s reading program “matches” and where it “misses” the instruction components recommended in this article. To document what you find, you may find our worksheets helpful.

- Find out if the instruction model your child’s teacher uses is Direct Instruction, Strategy Instruction, or a combination approach. Some program literature states which approach a teacher should use; in other cases, it’s up to the teacher to decide. Compare the approach used to what this article describes as being most effective for addressing your child’s area of need.

- Once you’ve evaluated your child’s reading program, you may feel satisfied that her needs are being met. If not, schedule a conference with her teacher (or her IEP team, if she has one) to present your concerns and discuss alternative solutions.

Hope and hard work — not miracles

Finally, Dr. Swanson cautions, “There is no ‘miracle cure’ for reading disabilities. Even a reading program that has all the right elements requires both student and teacher to be persistent and work steadily toward reading proficiency.”

But knowledge is power, and the findings of Dr. Swanson’s study offer parents and teachers a tremendous opportunity to evaluate and select reading interventions most likely to move kids with LD toward reading success.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D

The school bell may stop ringing, but summer is a great time for all kinds of educational opportunities. Children with learning disabilities particularly profit from learning activities that are part of their summer experience — both the fun they have and the work they do.

Beautiful Minds Inc. found Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D. has packed this virtual Beach Bag of activities for teachers to help families get ready for summer and to launch students to a fun, enriching summer.

In the virtual Beach Bag you’ll find materials you can download and distribute, but you’ll also find ideas for things that you may want to gather and offer to students and parents and for connections you’ll want to make to help ensure summer learning gain rather than loss.

– Put an article on strategies for summer reading for children with dyslexia in your school or PTA newsletter. Send it home with your students to the parents.

If many of your students go to summer camp, send the parents When the Child with Special Needs goes off to Summer Camp an article by Rick Lavoie which tells parents what to do to support their children during camp.

– Teach them an important skill they can use over the summer. Read Teaching Time Management to Students with Learning Disabilities to learn about task analysis, which families can use to plan summer projects.

– Make sure your students are able to read over the summer — put books into children’s hands. Register with First Book and gain access to award-winning new books for free and to deeply discounted new books and educational materials.

– Tell your parents about Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, which allows their children to listen to books over the summer.

– Encourage writing. Send The Writing Road home to your parents so they can help their children. Give each of your students a stamped, addressed postcard so they can write to you about their summer adventures.

– Get your local public library to sign kids up for summer reading before school is out. Invite or ask your school librarian to coordinate a visit from the children’s librarian at the public library near the end of the school year. Ask them to talk about summer activities, audio books, and resources from the National Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Have them talk about summer activities at the library and distribute summer reading program materials.

– Study reading incentive programs by publishers and booksellers such as Scholastic’s Summer Reading Buzz, HarperCollins Children’s Books Reading Warriors, or the Barnes & Noble Summer Reading Program. If you think these programs will motivate your students, let the families know about them. Find ways to make accommodations so they can participate if necessary.

– Offer recommended reading. LD OnLine’s Kidzone lists books that are fun summertime reads. The Association for Library Services to Children, a division of the American Library Association, offers lists for summer reading. Or ask your school or public librarian for an age-appropriate reading list.

– Encourage your parents to set up a summer listening program which encourages their children to listen to written language. Research shows that some children with learning disabilities profit from reading the text and listening to it at the same time.

– Offer recommendations for active learning experiences. Check with your local department of parks and recreation about camps and other activities. Find out what exhibits, events, or concerts are happening in your town over the summer. Encourage one of your parents to organize families of children with learning disabilities together for learning experiences.

Dr. Ufondu also desires for parents to plan ahead. Work with the teachers a grade level above to develop a short list of what students have to look forward to when they return to school in the fall. Many kids with learning disabilities will want to study over the summer so that they can get a head start.

Ivory A. Toldson, Ph.D.

“Among the nearly 40,000 black male 9th graders currently in honors classes, 2.5% have been told they have a Learning Disability, 3.3% Autism, and 6% ADHD… Black males with and without disabilities can excel in schools that have adequate opportunities for diverse learners and a structure that supports personal and emotional growth and development”;

For the data presented in this report, the author analyzed 17,587 black, Hispanic, and white male and female students (black male N = 1,149) who completed the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (Ingels, et al., 2011). This is a brief report from a larger study completed under the auspices of the National Dropout Prevention Center for Students with Disabilities (NDPC-SD) for the United States Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP).

Research suggests that black boys’ transition to and through the ninth grade shapes their future odds of graduating from high school (Cooper & Liou, 2007). Today, approximately 258,047 of the 4.1 million ninth graders in the United States are Black males. Among them, about 23,000 are receiving special education services, more than 37,000 are enrolled in honors classes, and for nearly 46,000, a health care professional or school official has told them that they have at least one disability. If black male ninth graders follow current trends, about half of them will not graduate with their current ninth grade class (Jackson, 2010), and about 20 percent will reach the age of 25 without obtaining a high school diploma or GED (Ruggles, et al., 2009).

Black boys are the most likely to receive special education services and the least likely to be enrolled in honors classes. Across black, white and Hispanic males and females, 6.5 percent are receiving special education services, 9.7 percent have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), and 25 percent are in honors classes. For black boys, 9 percent are receiving special education services, 14.7 percent have an IEP, and 14.5 percent are enrolled in honors classes. Black boys who are in the ninth grade are more likely to be enrolled in honors classes than to receive special education services (SEE Table 1).

Having specific disabilities, including learning disabilities, developmental delays, autism, intellectual disabilities, or ADD/ADHD, increases the odds that any child will receive special education services. Among black male ninth graders who are currently receiving special education services, 84 percent have a disability and 15.5 percent have never been diagnosed. Among those not receiving special education services, 80 percent have never been indicated for a disability, and 20 percent have. Black males are no more likely to be diagnosed with a disability than white and Hispanic males (SEE Table 2).

Having a disability is related to other negative consequences, particularly for black males. Aside from special education, students with disabilities are more likely to (1) repeat a grade, (2) be suspended or expelled from school, (3) have the school contact the parent about problem behavior, and (4) have the school contact the parent about poor performance. When creating a scale which included the four risk factors mentioned, plus special education and having an IEP, black boys without disabilities were likely to endorse at least 1 of the 6 risk indicators, and those with disabilities endorsed between 3 and 4. Using these factors as a reliable predictor of not completing school, we find that students of all races and genders are at least three times more likely to drop out of school than their counterparts without disabilities. Among all races and genders, black males without disabilities endorsed more risk factors than others without disabilities, and black males with disabilities endorsed more risk factors than any other group of students (SEE Figure 1).

Nevertheless, the trajectory of black males with disabilities is not uniformly dismal. Among the nearly 40,000 black male ninth graders who are currently enrolled in honors courses, 15 percent have been told they had a disability by a health professional or the school at least once. Three percent of black males in honors courses have been told they have a learning disability, 3 percent autism and 6 percent ADD or ADH

How Black boys with Disabilities End up in Honors Classes

Having a broader understanding of the true nature of disabilities helps us to have a better understanding of how black boys with disabilities end up in honors classes. Importantly, a disability does not have to be debilitating. For instance, a learning disorder may be more aptly described an alternative learning style. For some students, mastering an alternative learning style will give them a competitive edge over students who are average “standard” learners. A visual learner could master the art of using pictures to encode lessons in their memory or use “concept mapping” to invigorate mundane text. Similarly, while some easy-to-bore ADD and ADHD students have an irresistible impulse to create the havoc necessary to stimulate their insatiable nervous system, others may use their urges to energize the lessons. They may interject humor and anecdotes, or push the teachers to create analogies. While they may have difficulty processing large volumes of dense text, they may be the best at taking discrete concepts and applying them creatively to novel situations

Every disability has a negative and positive offprint. Most are aware of the social challenges for children with autism that make it difficult for them to communicate with other students or teachers. However, few take the time to understand the advantages of certain peculiar behaviors. In some instances, children with autism are able to leverage their repetitive behaviors and extraordinary attention to random objects, into the development of mathematic and artistic abilities. Similarly, the scattered attention and hyperactive energy of someone with ADHD helps some children to juggle many task, relate to many people, and excel in student activities and student government. Many studies suggest that beyond school, people with symptoms of ADHD often excel in professional roles

How Black boys without Disabilities End Up in Special Education

Importantly, having or not having a disability is not a rigid category. Most, if not all, people have some characteristics of one or more disability. We all have different attention spans, levels of anxiety, susceptibility to distraction, social acuity, etc., which are controlled by past and present circumstances, as well as our unique biochemical makeup. Many black boys who end up in special education do not have a disability. Rather, they have circumstances that spur behavior patterns that are not compatible with the school environment. Situation specific symptoms will usually remit with basic guidance and structural modifications to the persons’ situation. In school settings, from the standpoint of disabilities, students can be divided into four categories:

A true negative – children who do not have a disability and have never been diagnosed

A true positive – children who have a disability and have been accurately diagnosed

A false negative – children who have a disability but have never been diagnosed

A false positive – children who do not have a disability but have been diagnosed with one; or have a specific disability and diagnosed with the wrong one.

Many problems are associated with false negative and false positive diagnoses. A child with an undiagnosed disability might experience less compassion and no accommodations for learning or behavioral challenges. A child with a genuine learning disorder might be expected to follow the same pace as other students, and be penalized with suspension for opposing an incompatible learning process. False positive children may be relegated to a learning environment that is not stimulating or challenging. There is research evidence that Black males are more likely than other races to have false negative and false positive diagnoses, due to culturally biased assessments, unique styles of expression, and environmental stressors.

What does this all mean?

Black males with and without disabilities can excel in schools that have adequate opportunities for diverse learners and a structure that supports personal and emotional growth and development. Contrarily, schools that view disability and emotional adjustment difficulties as enduring pathologies that need to be permanently segregated from “normal” students, will stunt academic growth and development. The nearly 5,600 black male ninth graders with a history of disability who are currently enrolled in honors classes likely benefitted from patient and diligent parents who instilled a sense of agency within them, and a compassionate school that accommodates a diversity of learners. They are also likely to have some protection from adverse environmental conditions, such as community violence, which can compound disability symptoms.

Importantly, black males are no more likely to be diagnosed with a disability than Hispanic or white males, yet they are more likely than any other race or gender to be suspended, repeat a grade, or be placed in special education. Having a disability increases these dropout risk factors for all students regardless of race and gender; however, the tenuous status of black males in schools nationally appears to be due to issues beyond ability. One important caveat to consider: some studies suggest that come common drop out risk factors do not predict drop out for black males with the precision that it does for white males. For instance, frequency of suspensions has a much stronger association with dropping out (Lee, Cornell, Gregory, & Xitao, 2011) and delinquency (Toldson, 2011) for white males than it does for black males. The larger implication of this finding is very unsettling; while the act of suspending is reserved for the most deviant white male students, suspensions appear to be interwoven into the normal fabric black male’s school experiences.

While we cannot ignore the injustices in many schools, they should not overshadow the hope and promise of the black male students who are enrolled in honors classes. In addition, we should respectfully acknowledge schools and teachers who provide quality special education services designed to remediate specific educational challenges with the goal of helping students to reintegrate and fully participate in mainstream classes. Exploring the question, “how black boys with disabilities end up in honors classes, while others without disabilities end up in special education” may help us to gain a better understanding of an enduring problem, as well as reveal hidden solutions, for optimizing education among school-aged black males.