NEW YORK — She inspired a movement — and now she’s the youngest ever Time Person of the Year.

Greta Thunberg, the Swedish 16-year-old activist who emerged as the face of the fight against climate change and motivated people around the world to join the crusade, was announced Wednesday as the recipient of the magazine’s annual honor.

She rose to fame after cutting class in August 2018 to protest climate change — and the lack of action by world leaders to combat it — all by herself, but millions across the globe have joined her mission in the months since

“We can’t just continue living as if there was no tomorrow, because there is a tomorrow,” Thunberg told Time in the issue’s cover story. “That is all we are saying.”

The Person of the Year issue dates back to 1927 and recognizes the person or people who have the greatest influence on the world, good or bad, in a given year.

Since her protest, Thunberg has spoken at climate conferences across the planet, called out world leaders and refused to waiver in her quest to make an impact on the future.

Time editor-in-chief Edward Felsenthal acknowledged Thunberg as “the biggest voice on the biggest issue facing the planet” in an article explaining the 2019 selection.

“Thunberg stands on the shoulders — and at the side — of hundreds of thousands of others who’ve been blockading the streets and settling the science, many of them since before she was born,” he wrote. “She is also the first to note that her privileged background makes her ‘one of the lucky ones,’ as she puts it, in a crisis that disproportionately affects poor and indigenous communities. But this was the year the climate crisis went from behind the curtain to center stage, from ambient political noise to squarely on the world’s agenda, and no one did more to make that happen than Thunberg.”

In the cover story, Thunberg and her father reflect on her becoming depressed at 11 years old when a teacher introduced her class to the dire effects of climate change. The teenager’s diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, the magazine says, helped offer an explanation for why it affected her in that way.

“I see the world in black and white, and I don’t like compromising,” Thunberg told Time. “If I were like everyone else, I would have continued on and not seen this crisis.”

The selection of Thunberg was praised by Hillary Clinton, who tweeted that she “couldn’t think of a better Person of the Year.”

“I am grateful for all she’s done to raise awareness of the climate crisis and her willingness to tell hard, motivating truths,” Clinton wrote.

Thunberg herself was floored by the recognition.

“Wow, this is unbelievable!” she tweeted. “I share this great honour with everyone in the #FridaysForFuture movement and climate activists everywhere.”

This year’s Person of the Year runners-up were President Trump, the anonymous whistleblower who helped spark the Trump impeachment inquiry, Nancy Pelosi and the Hong Kong protestors.

In new categories, pop star Lizzo was named Entertainer of the Year by Time, the United States Women’s Soccer Team was selected as Athlete of the Year, and Bob Iger, the CEO of Disney, was named Business Person of the Year.

Meanwhile, foreign affairs specialist Fiona Hill, ambassadors William Taylor and Marie Yovanovitch, former White House official Mark Sandy, Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman and the whistleblower were recognized as “Guardians” for their public service.

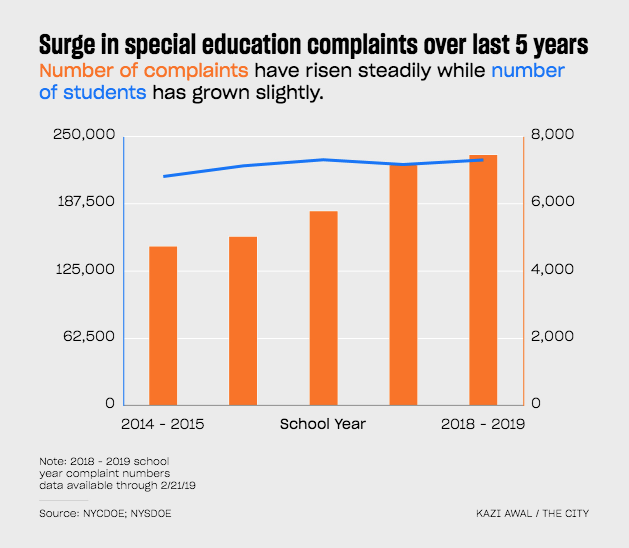

Complaints filed against the city Department of Education by parents of special education students have skyrocketed since 2014 — sparking a “crisis” that leaves some kids without essential service for months on end, a state-commissioned report found.

The flood of parents battling the public schools system for support is threatening to overwhelm a dispute-resolution system suffering from too few hearing officers and inadequate space to hold hearings, according to the external review obtained by THE CITY.

Complaints jumped 51 percent between the 2014-’15 and 2017-’18 school years, the report found. That surge has continued into the current school year, with 7,448 complaints filed as of late February — more than the total for the entire prior school year.

The average complaint was open for 202 days in 2017-’18, according to State Education Department data.

Growing complaints have caused a “crisis” that could “render an already fragile hearing system vulnerable to imminent failure and, ultimately, collapse,” Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, wrote in a 49-page report obtained through public disclosure law and provided to THE CITY.

“That it has not yet collapsed is remarkable given the staggering numbers of due process complaints filed in New York City.”

One family’s struggle

Brooklyn mom Josie Hernandez, who visited the DOE’s impartial hearing offices on Livingston Street in Brooklyn last week, said she’s been fighting to get her now 14-year-old son the services required under his individual education plan — known as an IEP — since October 2017.

The legally binding document says her son should be in a classroom capped at 12 students, and receiving speech therapy and counseling. But Hernandez says her son has never gotten all three of those requirements at any of the four schools he’s attended.

A recent neuropsych examination determined the teen is three or four grade levels behind, according to Hernandez.

“For three years, they’ve not been giving him the services mandated on the IEP,” she said. “Right now, he’s in a class with 19 kids.”

Rebecca Shore, director of litigation for the group Advocates for Children of New York, said parents file complaints for a host of reasons.

Some students are placed into schools that don’t offer programs mandated on their education plans. Others are thrust into classroom settings that don’t match those mandated by the IEP. In some cases, services called for in the IEP simply are not provided.

“When the parents come to us, unfortunately, usually it’s at a point where it’s been three or four or five or six years [without services],” said Shore, whose group provided the external review to THE CITY.

“At that point, the student needs a lot of compensatory services to make up for the lack of instruction and appropriate instruction the student experienced for that much time.”

Tuition reimbursement cases eyed

The report doesn’t attempt to identify why complaints are up. But it notes that some in the education field attribute the hike to a boost in parents using the due process system to seek tuition reimbursement for placing kids in private schools. That happens when the public school system can’t accommodate a student’s needs.

The number of students receiving reimbursement for private school tuition grew from 3,329 during the 2013-’14 school year to 4,431 in 2016-’17, according to the DOE.

The agency attributed the vast majority of complaint filings to tuition-reimbursement requests. Not all of those private school placements resulted, though, from due process complaints.

The DOE’s spending on the most common type of private school placement — known as Carter Cases — nearly doubled from $222 million to $417 million between the 2013 and 2016 school years, according to City Council budget documents.

Mayor Bill de Blasio announced in June 2014 that the city wouldn’t be as litigious as the prior administration in dealing with parent tuition-reimbursement requests. The requests hit a high in the 2016-’17 school year, the latest figures supplied by the DOE show.

The de Blasio plan called for an expedited process for a majority of those cases, in which the city would decide within 15 days whether to settle. But advocates say the much-heralded policy sparked a volume of filings that overwhelmed city workers and made the 15-day deadline impossible to meet.

“A significant amount of time has been spent trying to get these cases to settlement, so that process can sometimes take six to eight months itself,” said Nelson Mar, a senior staff attorney at Bronx Legal Services.

He noted the root of the problem is that public schools simply don’t have enough services to cover the needs of many of the city’s 224,000 special education students.

New York City logged more due process complaints than California, Florida, Texas and Pennsylvania combined, according to 2016-’17 data collected by the state Education Department.

“The reason why you’re seeing these astronomical numbers is because they have never addressed the fundamental problems with their delivery of special education services,” said Mar. “There’s not enough programs and not enough staff to provide services.”

City works on changes

While the external review was completed in February, the State Education Department didn’t release it publicly and instead included it as an appendix to a “Compliance Assurance Plan” produced by state officials earlier this month.

That plan detailed how New York City was out of compliance with federal law for the 13th straight year on its delivery of services for special education students. Among the issues raised: mandated services on student IEPs not being provided.

One of the reasons the complaint process moves so slowly in New York City is because the DOE isn’t trying to resolve enough cases through mediation, the plan noted. There were only 126 mediations held last year, according to state data.

The compliance report highlighted a number of other failings within the complaint system — which is run by the city but overseen by the state. One issue: 122 hearings are scheduled per day on average and there are only 10 hearing rooms.

And the hearing offices are all in downtown Brooklyn, an inconvenient location for many parents, the state plan noted. Plus, parents have to navigate through a connected lunchroom that doubles as a space for teachers who have been reassigned after being accused of misconduct.

State officials gave city education officials until June 3 to file a corrective action plan, which must include boosting the number of staffers at the impartial hearing office and adding hearing rooms.

City officials said they’re already implementing many of the requirements, while they’ve asked the state to certify more hearing officers.

“We’re committed to improving the impartial hearing process for families, and we’re hiring more impartial hearing staff and investing an additional $3.4 million to add impartial hearing rooms and make physical improvements to the impartial hearing office,” said Danielle Filson, a DOE spokesperson. “We’re also hiring more attorneys to reduce case backlog as part of a larger $33 million investment in special education, and we’re supporting the state as much as possible to hire more hearing officers.”

DOE officials said they’ve already moved the reassigned teachers from the lunchroom.

State officials said they’ve been pleased with city Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza’s actions on special education thus far.

“We are encouraged by Chancellor Carranza’s commitment to make the systemic changes necessary to transform the way New York City supports students with disabilities and we have already started to see improvements,” said state DOE spokesperson Emily DeSantis.

It’s that time of the year again Beautiful Minds families…Summertime! Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu lends us his recommendations for this year’s best and most fun summer camps for 2019. Summer camp can be a fun and exciting experience for children and adults with autism. Families can search for accredited summer camps on the American Camp Association website – they have thousands of listings, and there is an option to specify that you are looking for a camp serving children or young adults with autism.

Beautiful Minds Inc. is committed to promoting inclusion of children and adults with autism across all programs and organizations for families. Leading the Way: Autism-Friendly Youth Organizations is a guide to help organizations learn to integrate youth with autism into existing programs, communicate with parents, and train their staff. Please feel free to share this guide with any camps, sports programs, or other youth organizations your son might be interested in.

If you are looking for funding or financial assistance, many camps will offer tuition/fees on a sliding scale relative to your income. You can also find Family Grant Opportunities on our website.

Another option to consider is requesting an Extended School Year (ESY) program through your child’s school district or at the next IEP meeting. If there is evidence that a child experiences a substantial regression in skills during school vacations, he/she may be entitled to ESY services. These services would be provided over long breaks from school (summer vacation) to prevent substantial regression. This is usually discussed during annual IEP reviews but if you are concerned about regression, now is the best time to bring it up with your child’s team at school. Some children attend the camps listed in our Resource Guide as part of their Extended School Year (ESY) program.

Another good resource is MyAutismTeam, a social network specifically for parents of individuals with autism. Join more than 40,000 parents from all parts of the country and find parents whose children are similar to yours or who live near you, get tips and support, ask questions, and exchange referrals on great providers, services, and camps for your child.

Families can also reach out to the state’s Parent Training and Information Center to find additional information and support in their local areas.

New research by Morgan, Farkas, Hillemeier and Maczuga once again finds that when you take other student characteristics—notably family income and achievement—into account, racial and ethnic minority students are less likely to be identified for special education than white students.[1] Though this finding is by now well established, it remains sufficiently controversial to generate substantial media buzz.[2] And plenty of research—with less convincing methods—has been interpreted as showing that too many blacks, especially boys, are identified for special education.[3] The old conventional wisdom may be intuitively appealing because aggregate disability rates—with no adjustments for family income or other student characteristics—are higher for students who are black (1.4 times) or Native American (1.7), and lower for whites (0.9) and Asians (0.5), with Hispanic students about as likely to be identified as the rest of the population.[4]

These unadjusted ratios answer the important descriptive question of how student experience varies by race. But they do not tell us whether schools are giving black students the free and appropriate public education the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) guarantees them. To answer this question, we must compare the likelihood that a black student participates in special education with that of an otherwise identical white student. In other words, we don’t just want to know if black students are more likely to be in special education than whites; we want to know if black students are too likely to be in special education—or, as it turns out, not likely enough.

The conventional wisdom that blacks are over identified for special education may finally be losing ground among academics, but continues to influence public opinion and be reflected in federal law and policy. I recap this academic debate, and briefly review some major disparities we observe along racial and ethnic lines in income and other non-school factors likely to influence the need for special education by the time children enter school. I argue against fixed thresholds for how much variance states should tolerate in districts’ special education identification rates across racial and ethnic groups, and for comprehensive social policies to help address disparities in children’s well being.

THE DEBATE OVER OVER REPRESENTATION IN SPECIAL EDUCATION

In a 2002 National Research Council study, Donovan and Cross reviewed the literature and data on differences in special education participation by disability and racial/ethnic groups and cautioned against using unadjusted aggregate group-level identification rates to guide public policy.[5] They crystallized the challenge of interpreting these differences: “If… we are asking whether the number identified is in proportion to those whose achievement or behavior indicates a need for special supports, then the question is one for which no database currently exists.”[6]

Differences in aggregation, covariates, and samples generate different answers to the question of whether black students are over- or under-identified for special education.[7] The most credible studies allow researchers to control for a rich set of student-level characteristics, rather than using data aggregated to the district level, and firmly establish that blacks are disproportionately under-represented.

In 2010, Hibel, Farkas, and Morgan used the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study – Kindergarten Cohort (ECLS-K) 1998 and its follow-up waves to come closer to the ideal scenario described by Donovan and Cross.[8] While individual-level models controlling only for race and gender showed blacks more likely to be identified, adding a family socioeconomic status variable eliminated the effect of race for blacks, while Hispanics and Asians were significantly less likely to be in special education. Adding a student test score made blacks less likely to be identified; Hispanics and Asians remained less likely to be identified as well.

A follow up study found this result applied across the five disability classifications studied, notably including emotional disturbance and intellectual disability, stigmatizing categories in which black boys are over represented in the aggregate, unadjusted data.[9] While some have questioned the generalizability of the ECLS-K results due to sampling,[10] the qualitative result has been replicated using the National Assessment of Educational Progress (the 2017 Morgan et al. study), the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002,[11] and the ECLS-Birth Cohort.[12] These national patterns do not preclude local heterogeneity. Sullivan and Bal studied one Midwestern urban school district and found that while socioeconomic controls attenuate the impact of race, black students remain more likely than others to be identified for special education; they did not include student achievement as a covariate.[13]

THE “RIGHT” LEVEL OF IDENTIFICATION

Special education identification practices vary widely across and within states and districts – we do not know a “right” level. Few if any experts would argue that existing identification practices are ideal, or that identification rates reflect true prevalence of need. Beyond achievement and demographics, researchers have found that identification rates vary with school finance environments[14] and state accountability frameworks.[15]

If you view participation in special education as providing critical services to appropriately identified students, the fact that a given black student is less likely to be placed in special education than an otherwise identical white student is deeply troubling. We do not want to live in a society where parents describe access to dyslexia (or other) services as “a rich man’s game.”[16] It’s less troubling for those who view special education as stigmatizing and punitive, even for students who are appropriately identified — and indeed, we have little understanding of how well or poorly special education serves its students.

FEDERAL POLICY ON DISPROPORTIONALITY

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act aims to address equity by race and ethnicity; 2016 regulations further define the framework.[17][18] States must collect and review district-level data on how rates of identification—overall, by educational setting and disability category—vary across racial and ethnic groups with no adjustments for variables that correlate with need for services. If the gaps between groups exceed state-determined thresholds for “significant disproportionality,” the state must examine local policies and require the district to devote more of its federal special education funds to early intervention.[19]

While states will get to set their own cut-off risk ratios, they are highly unlikely to choose ratios that require uniform representation across groups. Each state then applies that threshold to all its districts. That means a district in which blacks and whites have similar poverty rates will be subject to the same threshold as one (in the same state) in which blacks have much lower income than whites.

REPORTING BY RACE AND ETHNICITY IS CRITICAL

REPORTING BY RACE AND ETHNICITY IS CRITICAL

Data on identification by race and ethnicity are essential for revealing patterns and outliers. They can prod districts and states to examine their special education policies and practices, potentially identifying ones that unintentionally yield discriminatory results, and shine a light on groups in need of greater early intervention resources.

According to Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Educational Psychologist and Founder of Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, “The preamble to the disproportionality regulations notes that unequal autism identification rates across groups may reflect disparities in access to medical care, suggesting that the district offer early developmental screenings.” Indeed, research shows that among Medicaid-eligible children with autism diagnoses, white children are diagnosed over a year earlier than black children.[20]

We do not want to live in a biased society where parents describe access to dyslexia (or other) services as “a rich man’s game.”

Dr. Ifeanyi A. Ufondu, Founder of Beautiful Minds Inc. – Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions

The Department of Education’s guidance notes that significant disproportionality could result from “appropriate identification, with higher prevalence of a disability, among a particular racial or ethnic group.” In other words, exceeding the risk ratio could be appropriate and acceptable: this level of nuance could easily be missed, while the state’s numeric threshold remains salient.[21]The result could be states and districts feeling pressured to produce equal rates of identification across groups—by denying services to students who need them. Unsurprisingly, Morgan and Farkas have argued against these regulations while offering up their own alternatives.[22]

UNADJUSTED DISPROPORTIONALITY REFLECTS MORE THAN EDUCATIONAL PRACTICES

Even if schools treated all students the same, special education identification rates would likely differ across racial and ethnic groups. The disproportionality literature consistently notes that children’s outcomes are causally affected by out-of-school factors such as poor nutrition, stress, and exposure to environmental toxins, and that exposure to these influences unduly affects poor children and children of color. The unfortunate implication of this—that true prevalence of disability may be higher for these students—can get lost in the back and forth over measurement, sampling, and other methodological issues. Some numbers are worth noting:

- Black children were three times as likely to live in poor families as white children in 2015. 12 percent of white and Asian children lived in poor families, compared with 36 percent of black children, 30 percent of Hispanic children, 33 percent of American Indian children, and 19 percent of others.[23]

- Food insecurity affects 23 percent of black-headed households and 19 percent of Hispanic-headed households, compared with 9 percent of households headed by whites.

- Black children are over twice as likely to have elevated blood lead levels as whites, and low-income children over three times as likely as others.[25]

- The poor are more likely to live near hazardous waste sites.[26]

WE NEED MORE COMPREHENSIVE SOCIAL POLICY TO HELP DISADVANTAGED CHILDREN

We need to work towards better identification practices in special education. We also need to help states and districts collect and report race- and ethnicity-specific rates. But forcing states to establish uniform standards is dangerously inconsistent with the IDEA mandate of a free and appropriate public education for all. When identifying another student pushes a district over a risk ratio threshold, the district faces a clear incentive to under identify—that is, to withhold services from—children who already face a broad array of systemic disadvantages.

Instead, we should focus on building a better safety net and reducing child poverty. Luckily, policymakers have plenty of proven levers: expand income support for families as the EITC,[27] reduce food insecurity while improving maternal health and birth outcomes through a robust SNAP,[28] maintain children’s access to Medicaid,[29] and continue to work towards improving the equity and quality of general education.[30]

While encouraging school districts to avoid “disproportionality” surely comes from an idealistic place, schools cannot do it alone. Ignoring the harsh realities of racial disparities outside of school is likely to hurt those very children advocates seek to protect.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D.

A worried mother says, “There’s so much publicity about the best programs for teaching kids to read. But my daughter has a learning disability and really struggles with reading. Will those programs help her? I can’t bear to watch her to fall further behind.”

Fortunately, in recent years, several excellent, well-publicized research studies (including the Report of the National Reading Panel) have helped parents and educators understand the most effective guidelines for teaching all children to read. But, to date, the general public has heard little about research on effective reading interventions for children who have learning disabilities (LD). Until now, that is!

This article will describe the findings of a research study that will help you become a wise consumer of reading programs for kids with reading disabilities.

Research reveals the best approach to teaching kids with LD to read

You’ll be glad to know that, over the past 30 years, a great deal of research has been done to identify the most effective reading interventions for students with learning disabilities who struggle with word recognition and/or reading comprehension skills. Between 1996 and 1998, a group of researchers led by H. Lee Swanson, Ph.D., Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of California at Riverside, set out to synthesize (via meta-analysis) the results of 92 such research studies (all of them scientifically-based). Through that analysis, Dr. Swanson identified the specific teaching methods and instruction components that proved most effective for increasing word recognition and reading comprehension skills in children and teens with LD.

Some of the findings that emerged from the meta-analysis were surprising. For example, Dr. Swanson points out, “Traditionally, one-on-one reading instruction has been considered optimal for students with LD. Yet we found that students with LD who received reading instruction in small groups (e.g., in a resource room) experienced a greater increase in skills than did students who had individual instruction.”

In this article, we’ll summarize and explain Dr. Swanson’s research findings. Then, for those of you whose kids have LD related to reading, we’ll offer practical tips for using the research findings to “size up” a particular reading program. Let’s start by looking at what the research uncovered.

A strong instructional core

Dr. Swanson points out that, according to previous research reviews, sound instructional practices include: daily reviews, statements of an instructional objective, teacher presentations of new material, guided practice, independent practice, and formative evaluations (i.e., testing to ensure the child has mastered the material). These practices are at the heart of any good reading intervention program and are reflected in several of the instructional components mentioned in this article.

Improving Word Recognition Skills: What Works?

“The most important outcome of teaching word recognition,” Dr. Swanson emphasizes, “is that students learn to recognize real words, not simply sound out ‘nonsense’ words using phonics skills.”

What other terms might teachers or other professionals use to describe a child’s problem with “word recognition”

- decoding

- phonics

- phonemic awareness

- word attack skills

Direct instruction appears the most effective approach for improving word recognition skills in students with learning disabilities. Direct instruction refers to teaching skills in an explicit, direct fashion. It involves drill/repetition/practice and can be delivered to one child or to a small group of students at the same time.

The three instruction components that proved most effective in increasing word recognition skills in students with learning disabilities are described below. Ideally, a reading program for word recognition will include all three components.

Increasing Word Recognition Skills in Students With LD

| Instruction component | Program Activities and Techniques* |

|---|---|

| Sequencing | The teacher:

|

| Segmentation | The teacher:

|

| Advanced organizers | The teacher:

|

* May be called “treatment description” in research studies.

Improving reading comprehension skills: What works?

The most effective approach to improving reading comprehension in students with learning disabilities appears to be a combination of direct instruction and strategy instruction. Strategy instruction means teaching students a plan (or strategy) to search for patterns in words and to identify key passages (paragraph or page) and the main idea in each. Once a student learns certain strategies, he can generalize them to other reading comprehension tasks. The instruction components found most effective for improving reading comprehension skills in students with LD are shown in the table below. Ideally, a program to improve reading comprehension should include all the components shown.

Improving Reading Comprehension in Students With LD

| Instruction component | Program Activities and Techniques* |

|---|---|

| Directed response/questioning | The teacher:

The teacher and student(s):

|

| Control difficulty of processing demands of task | The teacher:

The activities:

|

| Elaboration | The activities:

|

| Modeling of steps by the teacher | Teacher demonstrates the processes and/or steps the students are to follow. |

| Group instruction | Instruction and/or verbal interaction takes place in a small group composed of students and teacher |

| Strategy cues | The teacher:

The activities:

|

* May be called “treatment description” in research studies.

Evaluating your child’s reading program

Now you are well-equipped with research-based guidelines on the best teaching methods for kids with reading disabilities. At Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, we provide guidelines that will serve you well, even as new reading programs become available. To evaluate the reading program used in your child’s classroom, Beautiful Minds inc. founder, Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu recommends you follow these steps:

- Ask for detailed literature on your child’s reading program. Some schools voluntarily provide information about the reading programs they use. If they don’t do this — or if you need more detail than what they provide — don’t hesitate to request it from your child’s teacher, special education teacher, resource specialist, or a school district administrator. In any school — whether public or private — it is your right to have access to such information.

- Once you have literature on a specific reading program, locate the section(s) that describe its instruction components. Take note of where your child’s reading program “matches” and where it “misses” the instruction components recommended in this article. To document what you find, you may find our worksheets helpful.

- Find out if the instruction model your child’s teacher uses is Direct Instruction, Strategy Instruction, or a combination approach. Some program literature states which approach a teacher should use; in other cases, it’s up to the teacher to decide. Compare the approach used to what this article describes as being most effective for addressing your child’s area of need.

- Once you’ve evaluated your child’s reading program, you may feel satisfied that her needs are being met. If not, schedule a conference with her teacher (or her IEP team, if she has one) to present your concerns and discuss alternative solutions.

Hope and hard work — not miracles

Finally, Dr. Swanson cautions, “There is no ‘miracle cure’ for reading disabilities. Even a reading program that has all the right elements requires both student and teacher to be persistent and work steadily toward reading proficiency.”

But knowledge is power, and the findings of Dr. Swanson’s study offer parents and teachers a tremendous opportunity to evaluate and select reading interventions most likely to move kids with LD toward reading success.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D

The school bell may stop ringing, but summer is a great time for all kinds of educational opportunities. Children with learning disabilities particularly profit from learning activities that are part of their summer experience — both the fun they have and the work they do.

Beautiful Minds Inc. found Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Ph.D. has packed this virtual Beach Bag of activities for teachers to help families get ready for summer and to launch students to a fun, enriching summer.

In the virtual Beach Bag you’ll find materials you can download and distribute, but you’ll also find ideas for things that you may want to gather and offer to students and parents and for connections you’ll want to make to help ensure summer learning gain rather than loss.

– Put an article on strategies for summer reading for children with dyslexia in your school or PTA newsletter. Send it home with your students to the parents.

If many of your students go to summer camp, send the parents When the Child with Special Needs goes off to Summer Camp an article by Rick Lavoie which tells parents what to do to support their children during camp.

– Teach them an important skill they can use over the summer. Read Teaching Time Management to Students with Learning Disabilities to learn about task analysis, which families can use to plan summer projects.

– Make sure your students are able to read over the summer — put books into children’s hands. Register with First Book and gain access to award-winning new books for free and to deeply discounted new books and educational materials.

– Tell your parents about Recording for the Blind and Dyslexic, which allows their children to listen to books over the summer.

– Encourage writing. Send The Writing Road home to your parents so they can help their children. Give each of your students a stamped, addressed postcard so they can write to you about their summer adventures.

– Get your local public library to sign kids up for summer reading before school is out. Invite or ask your school librarian to coordinate a visit from the children’s librarian at the public library near the end of the school year. Ask them to talk about summer activities, audio books, and resources from the National Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Have them talk about summer activities at the library and distribute summer reading program materials.

– Study reading incentive programs by publishers and booksellers such as Scholastic’s Summer Reading Buzz, HarperCollins Children’s Books Reading Warriors, or the Barnes & Noble Summer Reading Program. If you think these programs will motivate your students, let the families know about them. Find ways to make accommodations so they can participate if necessary.

– Offer recommended reading. LD OnLine’s Kidzone lists books that are fun summertime reads. The Association for Library Services to Children, a division of the American Library Association, offers lists for summer reading. Or ask your school or public librarian for an age-appropriate reading list.

– Encourage your parents to set up a summer listening program which encourages their children to listen to written language. Research shows that some children with learning disabilities profit from reading the text and listening to it at the same time.

– Offer recommendations for active learning experiences. Check with your local department of parks and recreation about camps and other activities. Find out what exhibits, events, or concerts are happening in your town over the summer. Encourage one of your parents to organize families of children with learning disabilities together for learning experiences.

Dr. Ufondu also desires for parents to plan ahead. Work with the teachers a grade level above to develop a short list of what students have to look forward to when they return to school in the fall. Many kids with learning disabilities will want to study over the summer so that they can get a head start.

Ivory A. Toldson, Ph.D.

“Among the nearly 40,000 black male 9th graders currently in honors classes, 2.5% have been told they have a Learning Disability, 3.3% Autism, and 6% ADHD… Black males with and without disabilities can excel in schools that have adequate opportunities for diverse learners and a structure that supports personal and emotional growth and development”;

For the data presented in this report, the author analyzed 17,587 black, Hispanic, and white male and female students (black male N = 1,149) who completed the High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 (Ingels, et al., 2011). This is a brief report from a larger study completed under the auspices of the National Dropout Prevention Center for Students with Disabilities (NDPC-SD) for the United States Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP).

Research suggests that black boys’ transition to and through the ninth grade shapes their future odds of graduating from high school (Cooper & Liou, 2007). Today, approximately 258,047 of the 4.1 million ninth graders in the United States are Black males. Among them, about 23,000 are receiving special education services, more than 37,000 are enrolled in honors classes, and for nearly 46,000, a health care professional or school official has told them that they have at least one disability. If black male ninth graders follow current trends, about half of them will not graduate with their current ninth grade class (Jackson, 2010), and about 20 percent will reach the age of 25 without obtaining a high school diploma or GED (Ruggles, et al., 2009).

Black boys are the most likely to receive special education services and the least likely to be enrolled in honors classes. Across black, white and Hispanic males and females, 6.5 percent are receiving special education services, 9.7 percent have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), and 25 percent are in honors classes. For black boys, 9 percent are receiving special education services, 14.7 percent have an IEP, and 14.5 percent are enrolled in honors classes. Black boys who are in the ninth grade are more likely to be enrolled in honors classes than to receive special education services (SEE Table 1).

Having specific disabilities, including learning disabilities, developmental delays, autism, intellectual disabilities, or ADD/ADHD, increases the odds that any child will receive special education services. Among black male ninth graders who are currently receiving special education services, 84 percent have a disability and 15.5 percent have never been diagnosed. Among those not receiving special education services, 80 percent have never been indicated for a disability, and 20 percent have. Black males are no more likely to be diagnosed with a disability than white and Hispanic males (SEE Table 2).

Having a disability is related to other negative consequences, particularly for black males. Aside from special education, students with disabilities are more likely to (1) repeat a grade, (2) be suspended or expelled from school, (3) have the school contact the parent about problem behavior, and (4) have the school contact the parent about poor performance. When creating a scale which included the four risk factors mentioned, plus special education and having an IEP, black boys without disabilities were likely to endorse at least 1 of the 6 risk indicators, and those with disabilities endorsed between 3 and 4. Using these factors as a reliable predictor of not completing school, we find that students of all races and genders are at least three times more likely to drop out of school than their counterparts without disabilities. Among all races and genders, black males without disabilities endorsed more risk factors than others without disabilities, and black males with disabilities endorsed more risk factors than any other group of students (SEE Figure 1).

Nevertheless, the trajectory of black males with disabilities is not uniformly dismal. Among the nearly 40,000 black male ninth graders who are currently enrolled in honors courses, 15 percent have been told they had a disability by a health professional or the school at least once. Three percent of black males in honors courses have been told they have a learning disability, 3 percent autism and 6 percent ADD or ADH

How Black boys with Disabilities End up in Honors Classes

Having a broader understanding of the true nature of disabilities helps us to have a better understanding of how black boys with disabilities end up in honors classes. Importantly, a disability does not have to be debilitating. For instance, a learning disorder may be more aptly described an alternative learning style. For some students, mastering an alternative learning style will give them a competitive edge over students who are average “standard” learners. A visual learner could master the art of using pictures to encode lessons in their memory or use “concept mapping” to invigorate mundane text. Similarly, while some easy-to-bore ADD and ADHD students have an irresistible impulse to create the havoc necessary to stimulate their insatiable nervous system, others may use their urges to energize the lessons. They may interject humor and anecdotes, or push the teachers to create analogies. While they may have difficulty processing large volumes of dense text, they may be the best at taking discrete concepts and applying them creatively to novel situations

Every disability has a negative and positive offprint. Most are aware of the social challenges for children with autism that make it difficult for them to communicate with other students or teachers. However, few take the time to understand the advantages of certain peculiar behaviors. In some instances, children with autism are able to leverage their repetitive behaviors and extraordinary attention to random objects, into the development of mathematic and artistic abilities. Similarly, the scattered attention and hyperactive energy of someone with ADHD helps some children to juggle many task, relate to many people, and excel in student activities and student government. Many studies suggest that beyond school, people with symptoms of ADHD often excel in professional roles

How Black boys without Disabilities End Up in Special Education

Importantly, having or not having a disability is not a rigid category. Most, if not all, people have some characteristics of one or more disability. We all have different attention spans, levels of anxiety, susceptibility to distraction, social acuity, etc., which are controlled by past and present circumstances, as well as our unique biochemical makeup. Many black boys who end up in special education do not have a disability. Rather, they have circumstances that spur behavior patterns that are not compatible with the school environment. Situation specific symptoms will usually remit with basic guidance and structural modifications to the persons’ situation. In school settings, from the standpoint of disabilities, students can be divided into four categories:

A true negative – children who do not have a disability and have never been diagnosed

A true positive – children who have a disability and have been accurately diagnosed

A false negative – children who have a disability but have never been diagnosed

A false positive – children who do not have a disability but have been diagnosed with one; or have a specific disability and diagnosed with the wrong one.

Many problems are associated with false negative and false positive diagnoses. A child with an undiagnosed disability might experience less compassion and no accommodations for learning or behavioral challenges. A child with a genuine learning disorder might be expected to follow the same pace as other students, and be penalized with suspension for opposing an incompatible learning process. False positive children may be relegated to a learning environment that is not stimulating or challenging. There is research evidence that Black males are more likely than other races to have false negative and false positive diagnoses, due to culturally biased assessments, unique styles of expression, and environmental stressors.

What does this all mean?

Black males with and without disabilities can excel in schools that have adequate opportunities for diverse learners and a structure that supports personal and emotional growth and development. Contrarily, schools that view disability and emotional adjustment difficulties as enduring pathologies that need to be permanently segregated from “normal” students, will stunt academic growth and development. The nearly 5,600 black male ninth graders with a history of disability who are currently enrolled in honors classes likely benefitted from patient and diligent parents who instilled a sense of agency within them, and a compassionate school that accommodates a diversity of learners. They are also likely to have some protection from adverse environmental conditions, such as community violence, which can compound disability symptoms.

Importantly, black males are no more likely to be diagnosed with a disability than Hispanic or white males, yet they are more likely than any other race or gender to be suspended, repeat a grade, or be placed in special education. Having a disability increases these dropout risk factors for all students regardless of race and gender; however, the tenuous status of black males in schools nationally appears to be due to issues beyond ability. One important caveat to consider: some studies suggest that come common drop out risk factors do not predict drop out for black males with the precision that it does for white males. For instance, frequency of suspensions has a much stronger association with dropping out (Lee, Cornell, Gregory, & Xitao, 2011) and delinquency (Toldson, 2011) for white males than it does for black males. The larger implication of this finding is very unsettling; while the act of suspending is reserved for the most deviant white male students, suspensions appear to be interwoven into the normal fabric black male’s school experiences.

While we cannot ignore the injustices in many schools, they should not overshadow the hope and promise of the black male students who are enrolled in honors classes. In addition, we should respectfully acknowledge schools and teachers who provide quality special education services designed to remediate specific educational challenges with the goal of helping students to reintegrate and fully participate in mainstream classes. Exploring the question, “how black boys with disabilities end up in honors classes, while others without disabilities end up in special education” may help us to gain a better understanding of an enduring problem, as well as reveal hidden solutions, for optimizing education among school-aged black males.

By: Ifeanyi-Allah Ufondu, Marie Tejero Hughes, Sally Watson Moody, and Batya Elbaum

After discussion of each grouping format, implications for practice are highlighted with particular emphasis on instructional practices that promote effective grouping to meet the needs of all students during reading in general education classrooms. In the last 5 years, two issues in education have assumed considerable importance: reading instruction and inclusion. With respect to reading instruction, the issue has been twofold: (a) Too many students are not making adequate progress in reading), and (b) we are not taking advantage of research based practices in the implementation of reading programs. In the popular press the complexities and subtleties of this issue have been reduced to a simple argument between phonics versus whole language, but the reality is that there is considerable concern about the quality and effectiveness of early reading instruction. With respect to the second major issue of inclusion, considerable effort has been expended to restructure special and general education so that the needs of students with disabilities are better met within integrated settings. The result is that more students with disabilities receive education within general education settings than ever before, and increased collaboration is taking place between general and special education.

Both of these issues-reading instruction and inclusion-have been the topics for national agendas (e.g., President Clinton’s announcement in his State of the Union Address in 1996 that every child read by the end of third grade, Regular Education Initiative), state initiatives (e.g., Texas and California Reading Initiatives), and local school districts. The implementation of practices related to both of these issues has immediate and substantive impact on professional development, teaching practices, and materials used by classroom teachers.

Grouping practices for reading instruction play a critical role in facilitating effective implementation of both reading instruction and inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classes. Maheady referred to grouping as one of the alterable instructional factors that “can powerfully influence positively or negatively the levels of individual student engagement and hence academic progress”, as well as a means by which we can address diversity in classrooms. As increased numbers of students with learning disabilities (LD) are receiving education in the general education classroom, teachers will need to consider grouping practices that are effective for meeting these students’ needs. Furthermore, reading instruction is the academic area of greatest need for students with LD; thus, grouping practices that enhance the reading acquisition skills of students with LD need to be identified and implemented.

Until relatively recently, most teachers used homogeneous (same ability) groups for reading instruction. This prevailing practice was criticized based on several factors; ability grouping: (a) lowers self-esteem and reduces motivation among poor readers, (b) restricts friendship choices, and (c) widens the gap between poor readers and good readers. Perhaps the most alarming aspect of ability grouping was the finding that students who were the poorest readers received reading instruction that was inferior to that of higher ability counterparts in terms of instructional time; time reading, discussing, and comprehending text (Allington, 1980); and appropriateness of reading materials. As a result, heterogeneous grouping practices now prevail, and alternative grouping practices such as cooperative learning and peer tutoring have been developed.

As general education classrooms become more heterogeneous, due in part to the integration of students with LD, both special and general education teachers need to have at their disposal a variety of instructional techniques designed to meet the individual needs of their students. In this article, we provide an overview of the recent research on grouping. practices (whole class, small group, pairs, one-on-one) teachers use during reading instruction; furthermore, implications for reading instruction are highlighted after each discussion.

Whole-class instruction

Research findings

Considerable research has focused on the fact that for much of general education the instructional format is one in which the teacher delivers education to the class as a whole. The practice of whole-class instruction as the dominant approach to instruction has been well documented. For example, in a study that involved 60 elementary, middle, and high school general education classrooms that were observed over an entire year, whole-class instruction was the norm. When teachers were not providing whole-class instruction, they typically circulated around the room monitoring progress and behavior or attended to their own paperwork.

Elementary students have also reported that whole-class instruction is the predominant instructional grouping format. Students noted that teachers most frequently provided reading instruction to the class as a whole or by having students work alone. Students less frequently reported opportunities to work in small groups, and they rarely worked in pairs. Although students preferred to receive reading instruction in mixed-ability groups, they considered same ability grouping for reading important for nonreaders. Students who were identified as better readers revealed that they were sensitive to the needs of lower readers and did not express concerns about the unfairness of having to help them in mixed-ability groups. In particular, students with LD expressed appreciation for mixed-ability groups because they could then readily obtain help in identifying words or understanding what they were reading.

Many professionals have argued that teachers must decentralize some of their instruction if they are going to appropriately meet the needs of the increasing number of students with reading difficulties. However, general education teachers perceive that it is a lot more feasible to provide large-group instruction than small-group instruction for students with LD in the general education classroom. The issue is also true for individualizing instruction or finding time to provide mini lessons for students with LD. Teachers have reported that these are difficult tasks to embed in their instructional routines.

Implications for practice

Numerous routines and instructional practices can contribute to teachers’ effective use of whole-class instruction and implementation of alternative grouping practices.

Teachers can involve all students during whole-class instruction by asking questions and then asking students to partner to discuss the answer. Ask one student from the pair to provide the answer. This keeps all students engaged.

Teachers can use informal member checks to determine whether students agree, disagree, or have a question about a point made. This allows each student to quickly register a vote and requires students to attend to the question asked. Member checks can be used frequently and quickly to maintain engagement and learning for all students.

Teachers can ask students to provide summaries of the main points of a presentation through a discussion or after directions are provided. All students benefit when the material is reviewed, and a student summary allows the teacher to determine whether students understand the critical features.

Because many students with LD are reluctant to ask questions in large groups, teachers can provide cues to encourage and support students in taking risks. For example, teachers can encourage students to ask a “who,” “what,” or “where” question.

At the conclusion of a reading lesson, the teacher can distribute lesson reminder sheets, which all the students complete. These can be used by teachers to determine (a) what students have learned from the lesson, (b) what students liked about what they learned, and (c) what else students know about the topic.

Small-group instruction

Research findings

Small-group instruction offers an environment for teachers to provide students extensive opportunities to express what they know and receive feedback from other students and the teacher. Instructional conversations are easier to conduct and support with a small group of students. In a recent meta-analysis of the extent to which variation in effect sizes for reading outcomes for students with disabilities was associated with grouping format for reading instruction, small groups were found to yield the highest effect sizes. It is important to add that the overall number of small-group studies available in the sample was two. However, this finding is bolstered by the results of a meta-analysis of small-group instruction for students without disabilities, which yielded significantly high effect sizes for small-group instruction. The findings from this meta-analysis reveal that students in small groups in the classroom learned significantly more than students who were not instructed in small groups.

In a summary of the literature across academic areas for students with mild to severe disabilities, Polloway, Cronin, and Patton indicated that the research supported the efficacy of small-group instruction. In fact, their synthesis revealed that one-to-one instruction was not superior to small-group instruction. They further identified several benefits of small-group instruction, which include more efficient use of teacher and student time, lower cost, increased instructional time, increased peer interaction, and opportunities for students to improve generalization of skills.

In a descriptive study of the teacher-student ratios in special education classrooms (e.g., 1-1 instruction, 1-3 instruction, and 1-6 instruction), smaller teacher-led groups were associated with qualitatively and quantitatively better instruction. Missing from this study was an examination of student academic performance; thus, the effectiveness of various group sizes in terms of student achievement could not be determined.

A question that requires further attention regarding the effectiveness of small groups is the size of the group needed based on the instructional needs of the student. For example, are reading group sizes of six as effective as groups of three? At what point is the group size so large that the effects are similar to those of whole-class instruction? Do students who are beginning readers or those who have struggled extensively learning to read require much smaller groups, perhaps even one-on-one instruction, to ensure progress?

Although small group instruction is likely a very powerful tool to enhance the reading success of many children with LD, it is unlikely to be sufficient for many students. In addition to the size of the group, issues about the role of the teacher in small-group instruction require further investigation. In our analysis of the effectiveness of grouping practices for reading, each of the two studies represented different roles for the teacher. In one study, the teacher served primarily as the facilitator, while in a second study the teacher’s role was primarily one of providing direct instruction. Although the effect sizes for both studies were quite high (1.61 and .75, respectively), further research is needed to better understand issues related to a teacher’s role and responsibility within the group.

Implications for practice

Many teachers reveal that they have received little or no professional development in how to develop and implement successful instructional groups. Effective use of instructional groups may be enhanced through some of the following practices.

Perhaps the most obvious, but not always the most feasible application of instructional groups, is to implement reading groups that are led by the teacher. Whereas these groups have been demonstrated as effective, many teachers find it difficult to provide effective instruction to other members of the class while they are providing small-group instruction. Some teachers address this problem by providing learning centers, project learning, and shared reading time during small group instruction.

Flexible grouping has also been suggested as a procedure for implementing small-group instruction that addresses the specific needs of students without restricting their engagement to the same group all the time. Flexible grouping is considered an effective practice for enhancing the knowledge and skills of students without the negative social consequences associated with more permanent reading groups. This way teachers can use a variety of grouping formats at different times, determined by such criteria as students’ skills, prior knowledge, or interest. Flexible groups may be particularly valuable for students with LD who require explicit, intensive instruction in reading as well as opportunities for collaborative group work with classmates who are more proficient readers. Flexible grouping may also satisfy students’ preferences for working with a range of classmates rather than with the same students all of the time.

Student-led small groups have become increasingly popular based on the effective implementation of reciprocal teaching. This procedure allows students to take turns assuming the role of the leader and guiding reading instruction through question direction and answer facilitation.

Peer pairing and tutoring

Research findings

Asking students to work with a peer is an effective procedure for enhancing student learning in reading and is practical to implement because teachers are not responsible for direct contact with students. For students with LD involved in reading activities, the overall effect size for peer pairing based on a meta-analysis was ES = .37. This finding was similar to one reported for students with LD (ES = .36; Mathes & Fuchs, 1994) and for general education students (mean ES = .40).

The Elbaum and colleagues report revealed that the magnitude of the effects for peer pairing differed considerably depending on the role of the student within the pair. For example, when students with disabilities were paired with same-age partners, they derived greater benefit (ES = .43) from being tutored rather than from engagement in reciprocal tutoring (ES = .15). This may be a result that for the most part the tutors were students without disabilities who demonstrated better reading skills and were able to provide more effective instruction. These findings differ, however, when the peer pairing is cross-age rather than same-age. Overall, cross-age peer pairing students with disabilities derived greater benefit when they served in the role of tutor.

Students with LD prefer to work in pairs (with another student) rather than in large groups or by themselves. In fact, many students with LD consider other students to be their favorite teacher. Considering the high motivation students express for working with peers and the moderately high effect sizes that result from peer pairing activities for reading, it is unfortunate that students report very low use of peer pairing as an instructional procedure.

Implications for practice

Because students appreciate and benefit from opportunities to work with peers in reading activities, the following instructional practices may enhance opportunities for teachers to construct effective peer pairing within their classrooms.

Classwide Peer Tutoring (CWPT) is an instructional practice developed at Juniper Gardens to “increase the proportion of instructional time that all students engage in academic behaviors and provide pacing, feedback, immediate error correction, high mastery levels, and content coverage”. CWPT requires 30 minutes of instructional time during which 10 minutes is planned for each student to serve as a tutor, 10 minutes to be tutored, and 5 to 10 minutes to add and post individual and team points. Tutees begin by reading a brief passage from their book to their tutor, who in turns provides immediate error correction as well as points for correctly reading the sentences. When CWPT is used for reading comprehension, the tutee responds to “who, what, when, where, and why” questions provided by the tutor concerning the reading passage. The tutor corrects responses and provides the tutee with feedback.

Peer-Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS) borrows the basic structure of the original CWPT but expands the procedures to engage students in strategic reading activities. Students are engaged in three strategic reading activities more typically addressed during teacher directed instruction: partner reading with retell, paragraph summary, and prediction relay. PALS provides students with intensive, systematic practice in reading aloud, reviewing and sequencing information read, summarizing, stating main ideas, and predicting.

Think-Pair-Share hare was described by McTighe and Lyman as a procedure for enhancing student engagement and learning by providing students with opportunities to work individually and then to share their thinking or work with a partner. First, students are asked to think individually about a topic for several minutes. Then they are asked to work with a partner to discuss their thinking or ideas and to form a joint response. Pairs of students then share their responses with the class as a whole.

One-on-one instruction

Research findings

Traditionally, one-on-one instruction in which the student receives explicit instruction by the teacher is considered the most effective practice for enhancing outcomes for students with LD. In fact, the clinical model where the teacher works directly with the student for a designated period of time has a long standing tradition in LD. Most professionals consider one-on-one instruction to be the preferred procedure for enhancing outcomes in reading . Many professionals perceive one-on-one instruction as essential for students who are falling to learn to read: “Instruction in small groups may be effective as a classroom strategy, but it is not sufficient as a preventive or remedial strategy to give students a chance to catch up with their age mates”.

In a review of five programs designed for one-on-one instruction, Wasik and Slavin revealed that all of the programs were highly effective, even though they represented a broad range of methodologies. Though one-on-one instructional procedures are viewed as highly effective, they are actually infrequently implemented with students with LD, and when implemented, it is often for only a few minutes.

In a recent review of research on one-on-one instruction in reading, no published studies were identified that compared one-on-one instruction with other grouping formats (e.g., pairs, small groups, whole class) for elementary students with LD. Thus, though one-on-one instruction is a highly prized instructional procedure for students with LD, very little is known about its effectiveness.

Implications for practice

The implications for practice of one-on-one instruction are in many ways the most difficult to define because although there is universal agreement on its value, very little is known about its effectiveness for students with LD relative to other grouping formats. Furthermore, the instructional implications for practitioners revolve mostly around assisting them in restructuring their classrooms and caseloads so that it is possible for them to implement one-on-one instruction. Over the past 8 years we have worked with numerous special educators who have consistently informed us that the following factors impede their ability to implement one-on-one instruction: (a) case loads that often require them to provide services for as many as 20 students for 2 hours per day, forcing group sizes that exceed what many teachers perceive as effective; (b) increased requirements to work collaboratively with classroom teachers, which reduces their time for providing instruction directly to students; and (c) ongoing and time-consuming paperwork that facilitates documentation of services but impedes implementation of services.

Considering the “reality factors” identified by teachers, it is difficult to imagine how they might provide the one-on-one instruction required by many students with LD in order to make adequate progress in reading. Certainly, it would require restructuring special education so that the number of students receiving services and the amount of time these services are provided by special education teachers is altered.

Research studies have repeatedly shown that reading instruction in many classrooms is not designed to provide students with sufficient engaged reading opportunities to promote reading growth. We have provided a summary of recent research on the effectiveness for students with LD of various grouping practices that can increase engaged reading opportunities, as well as implications of this research for classroom instruction. As classrooms become more diverse, teachers need to vary their grouping practices during reading instruction. There needs to be a balance across grouping practices, not a sweeping abandonment of smaller grouping practices in favor of whole-class instruction. Teachers can meet the needs of all students, including the students with LD, by careful use of a variety of grouping practices, including whole-class instruction, teacher- and peer-led small group instruction, pairing and peer tutoring, and one-on-one instruction.

About the authors

Ifeanyi-Allah Ufondu, PhD, is the Nation’s leading Special Needs advocate and Educational Psychologist. He is also the founder of Beautiful Minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions. His current interests include best grouping practices for reading instruction and advocacy for At-Risk youth. Marie Tejero Hughes, PhD, is a research assistant professor in the School of Education at the University of Miami. Her research interests include parental involvement and instructional strategies for students with disabilities in inclusive settings. Sally Watson Moody is a senior research associate in the School of Education at the University of Miami. Her research interests include instructional grouping and effective reading instruction for students with learning disabilities. Batya Elbaum, PhD, is an assistant research professor in the School of Education at the University of Miami. Her primary research is on the academic progress and social development of students with learning disabilities.

By: Dr. Ifeanyi A. Ufondu, Founder

Along with new smiling faces, a new school year brings special education teachers new IEPs, new co-teaching arrangements, new assessments to give, and more. In order to help you be as effective as you can with your new students, we’ve put together our top 10 list of back-to-school tips that we hope will make managing your special education program a little easier.

1. Organize all that paperwork

Special educators handle lots of paperwork and documentation throughout the year. Try to set up two separate folders or binders for each child on your case load: one for keeping track of student work and assessment data and the other for keeping track of all other special education documentation.

2. Start a communication log

Keeping track of all phone calls, e-mails, notes home, meetings, and conferences is important. Create a “communication log” for yourself in a notebook that is easily accessible. Be sure to note the dates, times, and nature of the communications you have.

3. Review your students’ IEPs

The IEP is the cornerstone of every child’s educational program, so it’s important that you have a clear understanding of each IEP you’re responsible for. Make sure all IEPs are in compliance (e.g., all signatures are there and dates are aligned). Note any upcoming IEP meetings, reevaluations, or other key dates, and mark your calendar now. Most importantly, get a feel for where your students are and what they need by carefully reviewing the present levels of performance, services, and modifications in the IEP.

4. Establish a daily schedule for you and your students

Whether you’re a resource teacher or self-contained teacher, it’s important to establish your daily schedule. Be sure to consider the service hours required for each of your students, any related services, and co-teaching. Check your schedule against the IEPs to make sure that all services are met. And keep in mind that this schedule will most likely change during the year!

5. Call your students’ families

Take the time to introduce yourself with a brief phone call before school starts. You’ll be working with these students and their families for at least the next school year, and a simple “hello” from their future teacher can ease some of the back-to-school jitters!

6. Touch base with related service providers

It’s important to contact the related service providers — occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech/language therapists, or counselors — in your school as soon as possible to establish a schedule of times for your students who need these services. The earlier you touch base, the more likely you’ll be able to find times that work for everyone.

7. Meet with your general education co-teachers

Communicating with your general education co-teachers will be important throughout the year, so get a head start on establishing this important relationship now! Share all of the information you can about schedules, students, and IEP services so that you’re ready to start the year.

8. Keep everyone informed

All additional school staff such as assistants and specialists who will be working with your students need to be aware of their needs and their IEPs before school starts. Organize a way to keep track of who has read through the IEPs, and be sure to update your colleagues if the IEPs change during the school year.

9. Plan your B.O.Y. assessments

As soon as school starts, teachers start conducting their beginning of the year (B.O.Y.) assessments. Assessment data is used to update IEPs — and to shape your instruction — so it’s important to keep track of which students need which assessments. Get started by making a checklist of student names, required assessments, and a space for scores. This will help you stay organized and keep track of data once testing begins.

10. Start and stay positive

As a special educator, you’ll have lots of responsibilities this year, and it may seem overwhelming at times. If your focus is on the needs of your students and their success, you’ll stay motivated and find ways to make everything happen. Being positive, flexible, and organized from the start will help you and your students have a successful year.

For more information about starting the year off right, please visit our FAQ section