Black Boys and ADHD: Biology or Culture Clash?

By: Natalie Hopkinson

Repost: February 4, 2014

A black Brooklyn couple sit in their car waiting to hear what New York City’s elite Dalton School has to say about their son now. The dad wonders: “The question is, what is it about Idris that makes him disruptive?”

They take turns reading the school’s latest communiqué: “Talks out of turn continuously … impulse control. Has trouble respecting other students’ physical boundaries. [Needs to] focus on not distracting others.”

As we learn in the couple’s documentary film American Promise, which aired Monday on PBS and is available for streaming online starting today, the school suggested that the boy might have attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. When Idris was 4, the couple had him independently evaluated. They accepted the diagnosis but resisted prescription-drug treatment—at first. Later in the film, which follows their son and his best friend from kindergarten though high school graduation, Idris pleads with his parents to reconsider. His grades were mediocre. It might help, he reasoned.

When I saw this scene, my heart dropped—nearly as much as it did when young Idris said that he would be better off at his school if he were white.

I will admit to being one of those slightly paranoid black people who suspect that big pharma is trying to put us back in chains. But researchers have similar fears for a generation of kids of all races. In the recent New York Times investigation “The Selling of Attention Deficit Disorder,” prominent researchers called the marketing-driven explosion in diagnoses (600,000 in 1990 to 3.5 million today) a “national disaster of dangerous proportions.”

Black children are still diagnosed and medicated less frequently than white children, but they are catching up fast. Between 2001 and 2010, there was a 70 percent increase in diagnoses among black boys and girls ages 5 to 11, according to a Kaiser Permanente study released last year.

The increase in the number of diagnoses is positive in the sense that the stigma around having this and other neurological and mental disorders is melting away, and children are getting the help they need. But I fear that slick marketing (Maroon 5’s Adam Levine is the face of one ADHD campaign) and the academic pressure cooker is turning ADHD meds into performance-enhancing drugs for the classroom.

Some doctors admit to prescribing Adderall and other ADHD drugs to low-income kids, not because they have a disorder but just to help them do better in school. “We might not know the long-term effects, but we do know the short-term costs of school failure, which are real,” a pediatrician told the New York Times.

In some ways the disorder is becoming another way to keep up with the Joneses. In upper-middle-class communities, parents trade intelligence on compliant psychiatrists right along with good tutors. A white friend once advised me to get the diagnosis before my son reached seventh grade.

“After that it doesn’t count,” she said, meaning that you can’t qualify for extra time on the SAT. After high school, the medications are highly coveted on college campuses for students wanting to pull all-nighters.

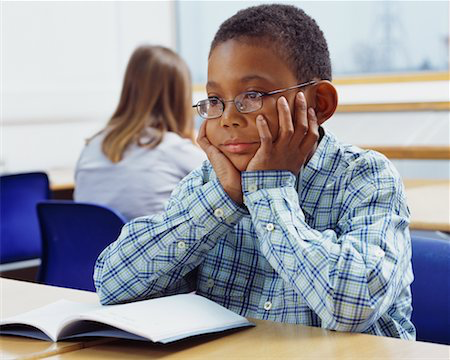

In my buppie parenting circles, we all seem to get the same not-so-subtle hints from school administrators about the deficiencies of our beautiful black sons. Is there something neurologically wrong with all of our boys? Or is something else in the culture at work? As one of the white Dalton administrators said, “There is a cultural disconnect between independent schools and African-American boys. The question is why.”

There are well-documented theories. Female-dominated classroom cultures punish boys. Toxic perceptions of black males in this country pollute the way schools interpret our boys’ behavior. There is pressure on teachers to maintain order in the classroom and produce results.

The ADHD drugs make boys more focused and compliant. But these medications can also potentially set them up for a lifetime of dependency and other side effects. Dr. Ifeanyi Ufondu, Educational Psychologist and founder of Beautiful minds Inc.- Advocacy & Special Needs Solutions, whom is also a veteran public school teacher and administrator in Los Angeles, CA, thinks that teachers and parents sometimes use the diagnosis as a crutch. “Sometimes it’s just poor teaching and not being in touch, culturally and socio-economically,” he said.

As the first male teacher at one high-poverty school, Ufondu worried about the prevalence of disciplinary referrals and the diagnosis in his male students. The boys were lethargic and complained of headaches and dry mouth. “Our boys appeared as zombies in the classroom,” he said. “They were constantly asking for water. You knew why they were behaving this way, but they were clueless,” Ufondu said.

But when the boys behaved poorly, parents were summoned to school. Single mothers especially couldn’t afford to constantly leave work, so the medication seemed like a godsend. But Ufondu convinced a group of parents to let him work with a group of second-grade boys on alternatives to medication. He created a structured system of routines with plenty of activities, short physical breaks and verbal prompts.

He knew some of the boys needed the medication to function normally. But over two years, for a majority of the group, Ufondu discovered dramatic improvement in both their behaviors and academic performance—with no medication. “They can avert the medication route,” Ufondu said. “They need to perfect the routine so they can get out their aggression in a healthy way. They need that release time to focus.”

The Brewster-Stephenson family came to a similar conclusion. Their son Idris used the medication for six months, and his academic performance soared, Brewster said in an interview with The Root. But Idris did not like the way the medication made him feel. So his parents took him off the prescription and used nonmedicinal interventions, including tutoring, rigidly scheduling his time and plenty of physical activity.

As a psychiatrist, Brewster is well aware of the resistance that black parents often have toward medicating their children and the highly subjective nature of how the disorder is diagnosed. “It is a highly personal and individual decision that families have to make,” he said.

If his son were at a public school, Brewster said, he probably would not feel the need to use medication. But they made the decision to put their son in the unforgiving academic environment and felt that they had to do whatever it took to help him succeed. They were very demanding of their firstborn son but made different choices for their younger son, who attends a more laid-back private school. “We also give him a lot more hugs,” Brewster said.

We all want our children to have the very best. We just have to decide if “success” on these terms is worth the price.

Natalie Hopkinson is a Washington, D.C.-based author whose current projects deal with the arts, gender and public life. She is the author of Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City. Follow her on Twitter.